Opera Atelier/Angel, text by John Milton and Rainer Maria Rilke, composed by Edwin Huizinga with Christopher Bagan, directed by Marshall Pynkoski, choreographed by Jeannette Lajeunesse Zingg, conducted by David Fallis, streaming Oct. 28 to Nov. 12. Tickets available here.

Internationally acclaimed company Opera Atelier specializes in period productions inspired by baroque opera-ballet, which features music, dance, acting and design in equal measure. Their newest production Angel, however, takes OA into new territory, namely, creating an original film.

Angel is a 70-minute opera ballet-cum-dramatic cantata. It is also a stream-of-consciousness meditation on good and evil, loss of innocence, and the role of angels. Along the way we get to meet three angels, four if you count Lucifer, Adam and Eve, and the Virgin Mary. As a film it is dense, opaque and quite beautiful.

The text has been cobbled together from John Milton’s monumental epic Paradise Lost (1663), and the mystic poetry of angel-obsessed Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (exquisitely translated by American author/playwright/poet Grace Andreacchi in an OA commission). It is Rilke’s lyrical contribution that makes the text dense and opaque (and anyone who has read Rilke knows what I mean).

Milton’s poetry contributes the straight-forward story-telling, while Rilke’s musings provide the philosophical and spiritual reflection. Clearly, an all-Rilke libretto would have been mystical overkill. No one person is credited with putting together the libretto, so I assume it was done by the creative team as a whole.

While there is some extant music in the piece by Matthew Locke (1621-1677), William Boyce (1711-1779), and Max Richter’s recomposition of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons (2012), which are primarily for the ballet sequences, the singing/choral component was specifically commissioned from composer Edwin Huizinga (with help from Christopher Bagan) as new music for baroque instruments, and what an interesting idea that is.

This production has an unusual history because it’s been assembled in increments. Between 2017 and 2020, Huizinga composed four scenes which were performed variously in Versailles, Chicago and Toronto. Angel incorporates these scenes, along with 40-minutes of new music, which includes Bagan’s contribution. What is interesting here is that despite the piecemeal creation, Angel does hang together as whole cloth.

Each of the three angels seems to have a different job. Tenor Colin Ainsworth is clearly a narrator who describes, in great torment, the fall of Lucifer. Soprano Measha Brueggergosman is also a narrator, but is a little more adventurous than Ainsworth, because she makes contact with Lucifer. She also appears to be the leader. To be crude, baritone Jesse Blumberg’s role would appear to be impregnating the Virgin (soprano Mireille Asselin).

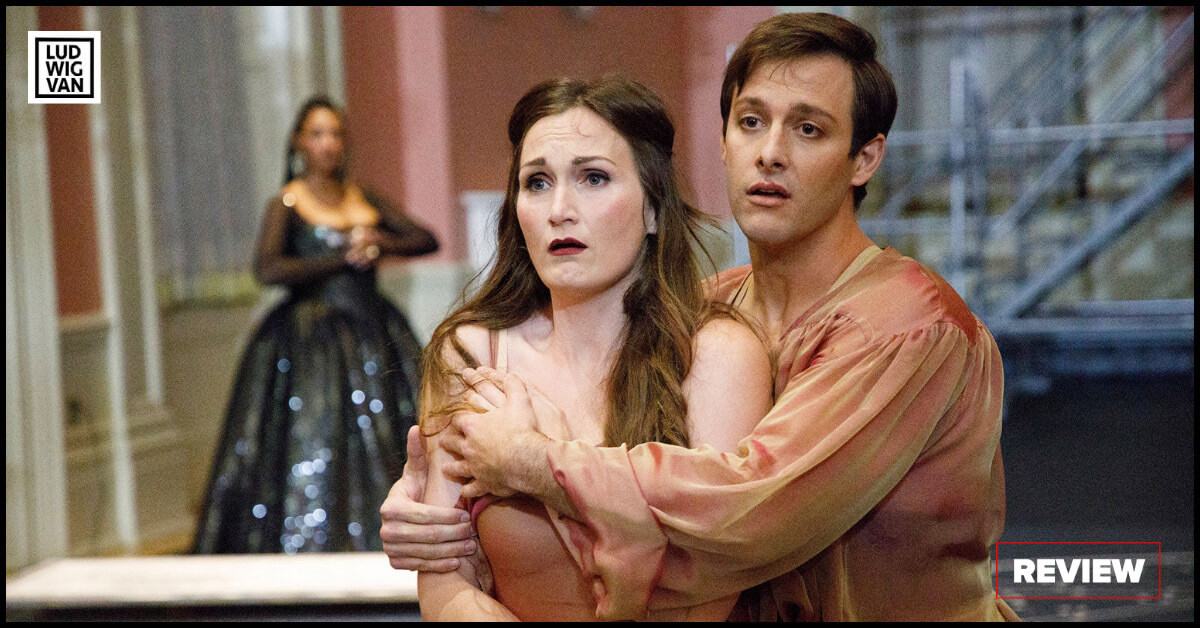

Adam (baritone John Tibbetts) and Eve (soprano Meghan Lindsay) are, according to Rilke, bereft at losing Eden, while Lucifer (bass-baritone Douglas Williams) is defiant. Though craving repentance, he will never submit to God, even though he realizes that he is doomed to live as the embodiment of Hell.

Huizinga’s music is modernist but not discordant, and he has included some nice touches. Ainsworth’s angel begins the piece with ferocious energy as he describes Lucifer’s fall. As for Lucifer, his music is positively anguished. Brueggergosman is given perhaps the most lyrical passages. For Adam and Eve, Huizinga has written a more simplistic, but eminently suitable vocal line. One of the loveliest sections has the Virgin as an echo to the angel’s seductive words. Needless to say, this is a company of strong singers, with Williams being a particular standout.

For me, among the most impressive aspects of Angel are the choral passages performed by the esteemed Nathaniel Dett Chorale. Under founder D. Brainerd Blyden-Taylor, I have always associated this choir with Afrocentric music, yet here they are performing in a classical context, and doing it superbly. Huizinga has given them both text and vocalise that is melodious and commanding, The composer clearly understands the dynamic between soloist and choral accompaniment.

The orchestra is, of course, OA’s long-time collaborator Tafelmusik, one of the greatest baroque ensembles on the planet, and they seem to have taken well to Huizinga’s new music for baroque instruments, with its quite convoluted orchestrations.

Tafelmusik’s uber-talented music director Elisa Citerrio gets to tackle with gusto the solo violin in the fiendish Richter/Vivaldi, while Huizinga himself appears in the film as a solo violinist for dancer Taylor Gledhill’s dark angel. Kudos, as always, to conductor David Fallis who puts the intention of the composer front and centre.

Zingg’s dance sequences, which range from baroque to ballet, in a form she cleverly calls 21st century baroque, appear to serve the purpose of a heavenly host. They anchor the libretto in the celestial realm. Garbed in lovely white dresses with tight bodices and full skirts for the women, and flowing shirts and leotards for the men, they float between the scenes like an army of angels, always bringing us back to the Heavens, and so to tranquillity and calm.

Dancer Tyler Gledhill created his own contemporary choreography for what appears to be a darker angel in his solo with Huizinga. He also mirrors Jesse Blumberg’s angel as he seduces the Virgin, thus bombarding her with both voice and movement. Zingg created a lovely solo for ballerina Julia Sedwick who represents the Virgin in the scene where Brueggergosman’s angel predicts her future.

Gerard Gauci’s set is dominated by the floor design. Apparently he found a website that shows you what the night sky looks like on a specific day over a specific place. Thus, the floor represents the exact constellations over Toronto on the day they started filming Angel. The set also includes a series of metal scaffolding that connotes the heavenly realm.

The designer also created the specific look for a naked Adam (with Tibbetts himself standing in) inspired by Notre Dame’s statue of Adam, situated beside the famous rose window. We see this statue before we actually meet Adam and Eve (in clothes). As art director for the film, Gauci also worked with filmmaker Marcel Canzona on creating a very nuanced light and colour palette for the film.

The costumes by Michael Gianfrancesco and Michael Legouffe would appear to be character specific. The women’s dresses are anchored in the baroque, with Brueggergosman’s being the most shimmery and elaborate. She also gets to wear actual wings. Ainsworth is encased in an over-sized black overcoat, while the men wear various attractive shirts and trousers. Alone among his fellows, Lucifer sports a green T-shirt. How the mighty have fallen.

Marcel Canzona is a one-man band as film director, editor and director of photography. He opted to film in black and white with a few touches of colour to represent the cosmos. While there are crossfades, superimposed images, and overhead shots, Canzona avoids overt trickery. What he has managed to capture is flow. The scenes blend beautifully together, from singers to dancers and back again. In fact, the editing is so smooth as to be almost imperceptible. And let’s send some praise to Matthew Antal, who supervised the audio production. The sound is gorgeous.

And of course, there is Pynkoski, whose fine hand embraces the whole project. Listed as stage director, I’m sure he supervised every aspect from soup to nuts concerning the production. This is the first OA undertaking conceived as a film, and it is a class act, from start to finish. Hypnotic, mesmerizing and totally otherworldly.

Some endnotes

I attended the premiere at TIFF so I saw Angel on the big screen which was a feast for the eyes. It was wonderful to be in a cinema once again. Maybe we are getting back to some kind of normalcy.

Those of us at the TIFF screening were given a special treat. Soprano Measha Brueggergosman, who is OA artist in residence, gave a mini concert performing songs by Reynaldo Hahn and Henry Purcell, accompanied by very simpatico pianist Christopher Bagan. She also sang the a cappella gospel number Over My Head.

When you’re dealing with a film of new music for baroque instruments, what music do you use for the opening and closing credits? I don’t know who thought of this, but it was brilliant as well as surprising. What we heard was a percussion solo performed by Naghmeh Farahmand on a variety of Middle East instruments — and it worked.

The ending of the film is not a happy one, which I think properly reflects the tenor of the times, though you could sense the surprise in the audience. There is no redemption. Lucifer, via Rilke, gets the final word.

Angel: Do you see Eden?

Lucifer: Eden Burns.

Angel: Do you feel life?

Lucifer: Life destroys.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig van Daily — classical music and opera in five minutes or less HERE.

- INTERVIEW | Actor Diego Matamoros Takes On Icon Walt Disney In Soulpepper Production Of Hnath Play - April 16, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Opera In Concert Shine A Light On Verdi’s Seldom Heard La Battaglia Di Legnano - April 9, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Lepage & Côté’s Hamlet Dazzles With Dance And Stagecraft Without Saying Anything New - April 5, 2024