Choreographer Crystal Pite’s Body and Soul, Performed By The Legendary Paris Opera Ballet, Kicks Off The Digidance Series, Streaming February 17 to 23.

No doubt dance concerts have been hard hit by the pandemic, but four of Canada’s leading dance presenters have banded together to try and redress the problem. The National Arts Centre (Ottawa), Danse Danse (Montreal), Harbourfront Centre (Toronto) and DanceHouse (Vancouver) have created a series called Digidance, the purpose being to put full-length quality dance programming online for audiences across Canada.

First up is Crystal Pite’s acclaimed 2019 work Body and Soul which she set on the Paris Opera Ballet, one of the most vaunted companies in the world. This streaming of Body and Soul is a Canadian exclusive, and we are the first international audience to experience this dancefilm.

Vancouver-based Pite has an international reputation for fearlessly working with large numbers of dancers. For example, Body and Soul features 36 of the Paris Opera Ballet’s brightest and best. She is an intellectual, and her choreographies are imbued with substantive content that runs deep. Pite is also an experimentalist who keeps pushing the boundaries of choreographic language. Using the exciting combination of Pite and the Paris Opera Ballet to inaugurate Digidance bodes well for the future of the series.

I reached Pite in Vancouver by phone.

What was it like working with the Paris Opera Ballet? The cut-throat, competitive nature of the company has been compared to the court of the Borgias.

This is my second piece for them. I set The Seasons’ Canon in 2016. Body and Soul premiered in 2019. The first time I was there was like going to another planet, and I was really nervous. You could even say I was full of terror because beginning a new creation is always like that. You also feel the weight of the famous Palais Garnier opera house itself, and the history and legacy of the legendary dancers who have performed there. And then there’s the pressure of expectations, but after about eight minutes in a room full of dancers, I felt okay.

They were all so welcoming, and you could sense how hungry they were for something new. There was real passion during the rehearsal process. It’s true that you can feel exhausted by the institution itself. The company has 154 dancers. It’s huge, but just being there as a guest meant I didn’t have to play politics. As well, I knew most of the cast, which I picked myself, and what was most thrilling was seeing how they had evolved as dance artists in the last three years.

These big ballet companies don’t allow a lot of time for rehearsals. How did you cope?

I had just eight or ten weeks to work in, which is a pretty tight time frame, so I arrived with ideas. I had a basic structure and content, which included big chunks of choreography. I was able to work out group ensembles here in Vancouver, with students from the Arts Umbrella, which is a non-profit centre for youth arts education. I’ve been associated with Arts Umbrella for years, and I couldn’t have created my big pieces for the National Ballet of Canada, Royal Ballet and the Paris Opera Ballet without them. It was labour intensive. I came with the group choreography, but I built the solos and duets on the dancers themselves during rehearsals in Paris.

What was the inspiration for Body and Soul?

When I was creating Revisor with Jonathon Young, I wrote a small scrap of text as something to begin experimenting with. We worked on it for a day and then discarded it, but I kept it in my back pocket, so to speak. It was this text that was the wellspring for Body and Soul. It’s written like stage directions — just describing two Figures in conflict by purely physical terms. “The lights snap on overhead. Interior. Two Figures are seen. One is on the floor. The other is moving back and forth. The conflict escalates into physicality.” That sort of thing.

The text was translated into French, and the voice-over is read by the acclaimed French film and stage actor Marina Hands. The text is repeated many times, but even though the words never change, with each iteration, they take on new meaning as the dancers embody them. Through the voice-over, the narrator joins our intricate onstage adventure world as both a pilgrim and a guide. My composer Owen Belton has also sampled the spoken text and used it as part of the score.

Where did this text lead you in terms of theme?

It’s a simple and short answer — conflict, connection, embodiment. Like carefully contained brush strokes, my work starts from small things and turns into big urgent pieces. In Body and Soul, we start with Figure One and Figure Two, but then these Figures can also represent more people, or even a different species. For example, a duet can be between two people, but it could also be between an individual and the group. The energizing tension of conflict can lead to many things. I explore conflict on the macro level, meaning it is the subject of the whole work, and on the micro level, which is conflict within the individual body.

On the other hand, connection is almost more important in Body and Soul. Everything I do involves connectedness. I want to connect performer to audience, and audience members to each other. Connectedness is also manifested in the structure of the work, and in what happens in the body. I’m also exploring how language can impact choreography. The conflict/connection duality is very powerful. Duets can happen between two people, between language and body, and between body and soul.

Body and Soul is in three parts. Can you describe them?

There are three very different worlds. The first part is a black box with one ginormous light fixture, so the overhead lights do snap on. Here we introduce the repetitive text, so the audience can become familiar with the words. People are identifiable, clothed in pants, suits, coats. In the second part, the dancers are wearing less clothes. The text also disappears for a while, and we have the music of Chopin, 24 Preludes.

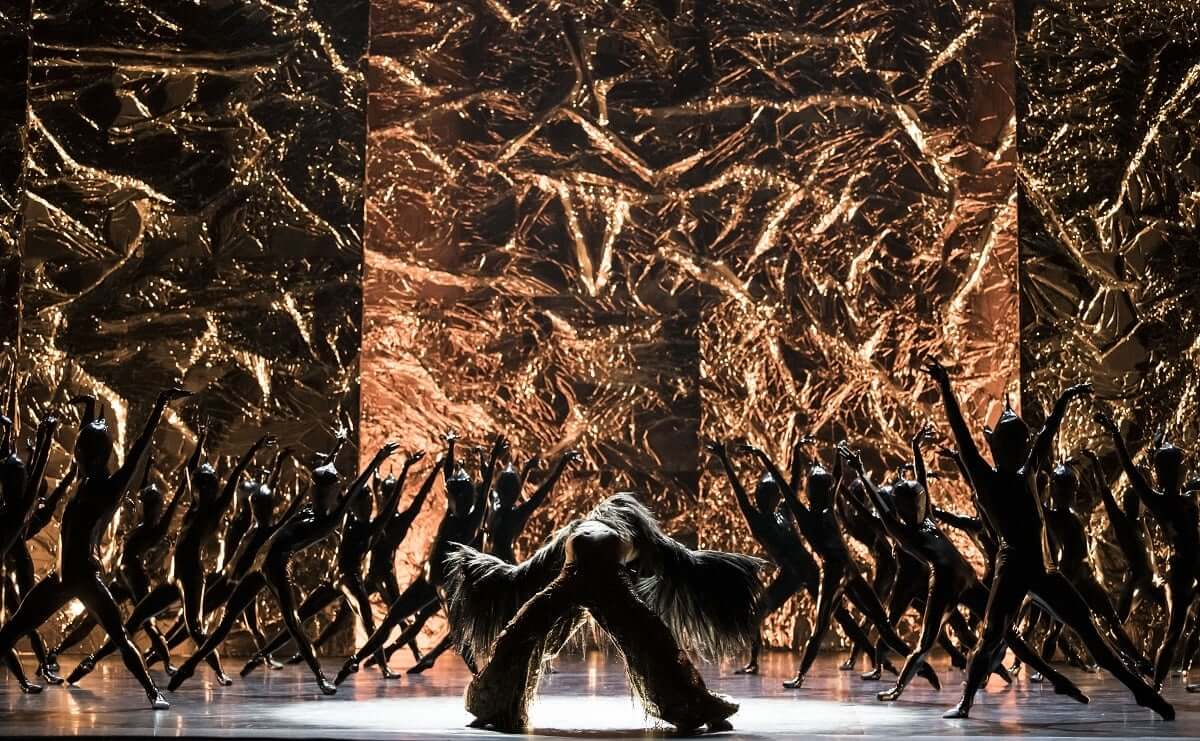

The third part is more detailed and produced. It is theatrical magic. My costume designer, Nancy Bryant, and I designed a costume that turns the dancers into a swarm of dangerous insect-like creatures. Prosthetic pieces extend the arms, and they have thorny protuberances on the body. It’s the same idea as Emergence that I did for National Ballet. We are in an otherworldly state. The dancers are creatures or aliens. The dance is decentralized into larger forms and groups, and the women are on point.

Talk about the music, which I assume is a mix of Owen’s electronica and Chopin.

While you hear the text and Chopin independently, Owen has also taken portions of the source and sampled them, which creates a different sound and feeling. For the creatures he has developed a clicking sound. As for the choice of Chopin, I love the Preludes. I’m also fascinated by the fact that when an audience is familiar with the music, the space becomes a commune that we share. The music affects how we see, how we hear, how we move. The connection between the body and music is a powerful thing.

Body and Soul was a piece that was performed live in the theatre. How do you feel about a dancefilm?

I choreograph in terms of the big wide shot. I see the stage only. On the other hand, Body and Soul has been transformed into a beautifully shot and edited archive. It’s not a dancefilm, in and of itself, because it wasn’t created as dance for the camera, but I appreciate its visual value. The Paris Opera Ballet is very protective about works it commissions, so great care was taken with the filming. Tommy Pascal was the filmmaker, and most importantly, he was a former dancer who performed with both Béjart Ballet and Ballet Preljocaj. He understands dance.

The filming was done over three performances, two before an audience and one that was dedicated to the camera. That way Tommy could use equipment he couldn’t if there was an audience in the house, like a tracking camera, which is a camera on a crane for those soaring overhead shots. Tommy came to Vancouver, so we could edit it together. I’d also like to say that, while I’m happy to share Body and Soul with my fellow Canadians, I want to add a disclaimer. I wish the audience could experience the work in a theatre where the dancers are at their most exposed. This film version, however, is the next best thing.

Getting asked once to create a work for the Paris Opera Ballet is a real coup, but to be asked a second time is pure gold.

It was particularly heartening when artistic director Aurélie Dupont invited me back, because at the time, A Seasons’ Canon hadn’t even had its premiere, and I was at my most vulnerable.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig van Daily — classical music and opera in five minutes or less HERE.

- INTERVIEW | Actor Diego Matamoros Takes On Icon Walt Disney In Soulpepper Production Of Hnath Play - April 16, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Opera In Concert Shine A Light On Verdi’s Seldom Heard La Battaglia Di Legnano - April 9, 2024

- SCRUTINY | Lepage & Côté’s Hamlet Dazzles With Dance And Stagecraft Without Saying Anything New - April 5, 2024