Robert Wilson’s 21st-century interpretation of Turandot is intriguing to be sure, but is it still Puccini?

Puccini: Turandot: Tamara Wilson (sop.), Joyce El-Khoury (sop.), Sergey Skorokhodov (ten.), David Leigh (bs), Adrian Thompson (ten.), Joel Allison (b-bar.), Adrian Timpau (bar.), Julius Ahn (ten.), Joseph Hu (ten.), Matthew Cairns (ten.); Robert Wilson, stage director and set designer; Canadian Children’s Opera Company, Teri Dunn, director; COC Chorus, Sandra Horst, chorus master; COC Orchestra, Carlo Rizzi, conductor. September 28, 2019, Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts.

Premiered in 1926, Puccini’s Principessa di gelo is 93. At such a grand age, her hold on the opera public remains as strong as ever. Based on performance statistics from 2004 to 2018, Turandot ranks 15th amongst all operas, with a total of 3,354 performances in 718 productions worldwide. While it ranks only fourth among Puccini operas, trailing La boheme, Tosca, and Madama Butterfly, it beats out such warhorses as Lucia di Lammermoor (18th), Il Trovatore (19th) and Otello (25th).

The reason for its popularity is easy to understand: an archetypal and enduring love story set in exotic Imperial China, seen through the Eurocentric lens of its creator. It deals with love in all its guises, not to mention filial piety, torture, execution, self-sacrifice, and the transformative power of love — all ideal fodder for grand opera.

Turandot is nothing if not grand. If the opera company’s budget allows, Turandot productions are a sort of “Operatic Cecil B. Demille,” with the company pulling out all the stops to present a spectacle. By coincidence, the best example of this genre is the Metropolitan Opera production of Turandot which opera fans can catch in Cineplex cinemas on October 12. “Grand” is an understatement when it comes to the Met production by that master of excess, Franco Zeffirelli.

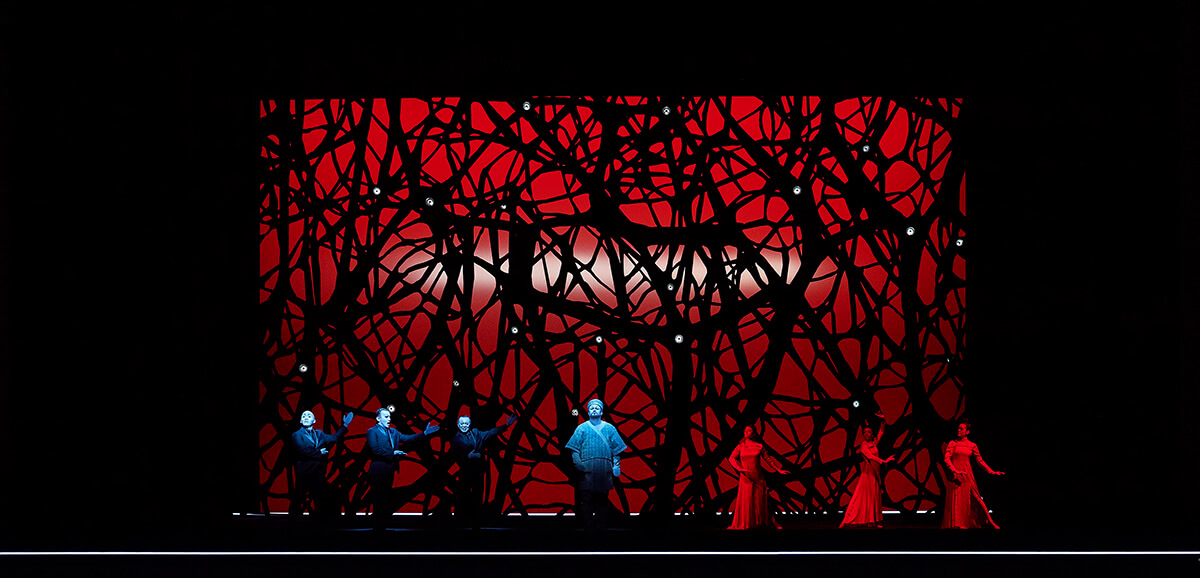

Anyone expecting similar treatment in the COC production by American stage director Robert Wilson will be sorely disappointed. Wilson’s aesthetics in stage design and direction is formalist and minimalist, pared-down, understated, all actions glacial, and frankly light-years away from the typical Zeffirelli. In the Wilson Turandot, colour use is singular in palette, and with not a hint of chinoiserie, let alone curlicues.

What Wilson does have is painting by colour and light. Stage movements and hand/arm gestures are highly choreographed and restricted, often with meanings that are obscure to the audience. Performers invariably face the auditorium, with little interaction with among them. Naturalism is not part of the Robert Wilson vocabulary.

Given the rigidity of Wilson’s formalism, there are often discrepancies between the text and the staging. Sometimes, it’s said that a pared-down treatment frees a work from its historically bound traditions, allowing the audience to focus on the music. A contrarian view would argue that the Wilson aesthetic is a stylistic straitjacket that is imposed on any and all opera, suitable or not.

A case in point is the comparison of the current Turandot with Wilson’s Einstein On The Beach, seen in Toronto during the Luminato Festival in 2012. At four and a half hours, it was a marathon, especially without an intermission, although the audience was free to come and go at will. I was so mesmerized that I sat through the whole duration without a washroom break. Wilson’s sparse style suits the minimalism of the Phillip Glass score.

By contrast, the Wilson aesthetic proves problematic in Turandot, and I dare say in most Puccini and verismo operas, where passion rules. While his stage design (particularly in his use of light) and directorial styles may create visually striking images, the lack of physical contact also contributes a sense of coldness and isolation, at the expense the requisite interrelatedness between the characters, so important in a human drama.

The Wilson Turandot must be the first production in history where the lovers never looked at each other — never mind touched. The requisite kiss is missing, barely symbolized by Calaf touching his lips with two fingers and then flicking it in thin air. No embracing in the final tableau — here the spotlight is on Turandot standing front and center, while Calaf is nowhere to be seen.

Instead of the transformative power of love, what we get is the not-so-subtle feminist message that this Turandot is going at it alone in the world, with or without a man in her life. Perhaps a bit of 21st-century revisionist interpretation? Intriguing to be sure, but is it Puccini?

Musically, it is indeed Puccini at his most resplendent, thanks to an exceptional cast and superlative orchestral playing under the baton of Maestro Carlo Rizzi. An old hand in the Italian standard repertoire, Rizzi conducted with great authority and incisiveness — and without a score — drawing magnificent sounds from the pit.

The excellent cast was led by American soprano Tamara Wilson in her first Turandot, and it was an outstanding achievement. Essentially a bright-voiced lirico-spinto, Wilson shows in no uncertain terms that she’s ready for the true dramatic roles the likes of Turandot. Her sound is perfectly focused that carries to the galleries. Yet it’s not all about power — she sang with exemplary nuance, all the chiaroscuro one would want. Turandot is destined to be a signature role for her.

Matching her note for note was debuting Russian tenor Sergey Skorokhodov, offering bright tone and a secure top register up to a clarion high C. Canadian soprano Joyce El-Khoury returns to the COC as Liu, a role that shows off her incomparable high pianissimi. Bass David Leigh (Timur), last heard in Hadrian, looked awesome in a long white wig and sang with sturdy tone. As Emperor Altoum, British tenor Adrian Thompson deserves hazard pay for stationed the whole time on a swing 30 feet in the air.

All the supporting roles were well taken. The trio of Ping/Pang/Pong (baritone Adrian Timpau, tenor Julius Ahn, and tenor Joseph Hu) was terrific, with Moldovan baritone Timpau deserving of special mention for his exceptionally beautiful lyric baritone. It made the extra shenanigans dreamed up for them by Wilson almost tolerable.

COC Ensemble bass-baritone Joel Allison was excellent as a sonorous-sounding Mandarin, the first voice heard in the opera. Prince of Persia in this production is only an off-stage voice, but COC first-year Ensemble tenor Matthew Cairns seized the moment and made a strong impression with his single line.

There you have it, a very good evening at the opera. Eight more performances to October 27. Details, here.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.

- SCRUTINY | Toronto Mendelssohn Choir Opens Season With Deeply Moving Brahms Requiem - November 10, 2025

- PREVIEW| A Critic’s Pick Of The Met Opera Live In HD 2025-26 Season - September 29, 2025

- SCRUTINY | Ukrainian Art Song Summer Institute 2025 Concert A Deeply Moving Experience - August 20, 2025