If you were watching the opening ceremonies of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, you might have taken in Lang Lang performing on a stunning nine-foot grand piano made of sparkling crystal. If you have a large screen TV, or saw other close-up footage, you might have noticed a detail that should have caught any Toronto music lover’s eye — the brand name of the piano was Heintzman. The piano was later auctioned off for $3.22 million, a record-setting price for a piano.

Heintzman, a part of Toronto’s history, and arguably the crown jewel of Canada’s storied piano making past. It’s a past that is long gone, but perhaps not entirely forgotten.

There was a time when many, perhaps even most, Canadian homes contained a piano. “In the early 1900s, there were 300-plus brands of Canadian pianos,” says James Musselwhite, a third generation piano technician with Paul Hahn & Co. “In that day and age, people might have had a Victrola. There was no TV, no radio.”

“Just about every home had a piano. That was home entertainment,” says Thomas Lawrie, a piano technician based in Grimsby, Ontario.

There were some early imports from the United States or Europe, but Canada was vast, and what’s more, had a wealth of raw materials. There was an abundance of wood, and with one of the continent’s largest steel foundries located in Hamilton, the pieces were in place. During the golden era of Toronto piano makers, roughly from 1900 to 1920, Toronto made instruments rivalled Europe’s legendary companies.

From the Daniel Bell Organ Co. to Whaley-Royce, Toronto has been home to 48 different piano companies, including several factories.

“It gets confusing because factories would make pianos with their own name, (and also) with a dealers’ name.” John Hall is a piano technician, piano collector, and the owner and curator of the Canadian Piano Museum in Napanee, Ontario. “Heintzman in Toronto sold Weber pianos, which were actually made in Kingston,” he says. Those Webers can be identified with the inscription “made for Heintzman” beside the Weber logo.

Canada’s piano making story begins before Confederation. Because of the distance and difficulty moving heavy pianos across the ocean, local manufacturers began to spring up quickly. The first Canadian builder was likely Frederick Hund in Québec City in 1816, and by mid-century, piano makers were popping up from Halifax to Toronto. The 1851 Upper Canada census lists four piano companies in Toronto.

Theodore Heintzman arrived in Toronto after having trained in Berlin and then New York City as a piano technician. He was building pianos by 1860. As legend would have it, he built his first piano on Canadian soil in his own kitchen and sold it for seed money to build his company, which he incorporated in 1866.

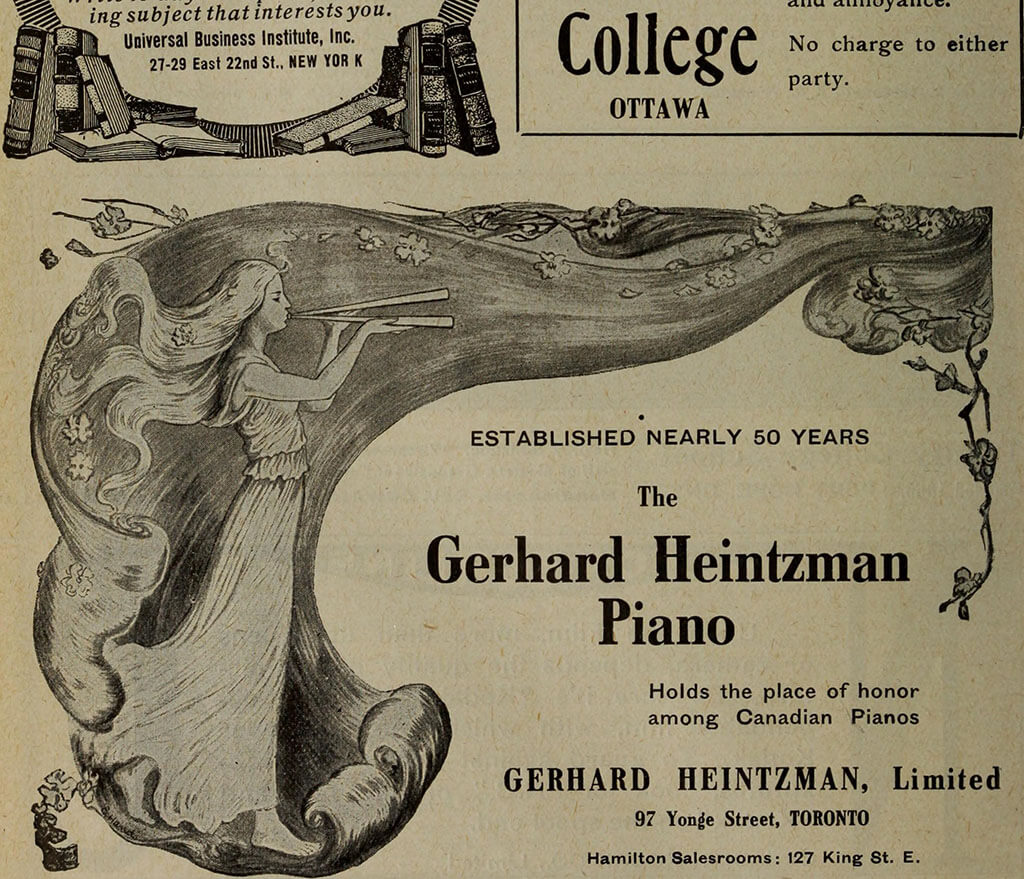

From the beginning, Heintzman aimed for the high-end of the market, and the highest quality instruments. From the 1890s to 1920s, the Heintzman name rivalled Steinway when it came to reputation among professional musicians and orchestras. Heintzman’s emphasis on quality and durability mean that there are many old instruments still in existence, and even century-old pianos are often still in good standing, and worthwhile restoring.

“Heintzmans are unusual pianos in that they were built to withstand any North American climate,” Musselwhite says. His father worked in the old Heintzman factory in the city’s west end, and James has firsthand memories of the operation. “The building was built like a brick rectangle with a hole in it.” The gap was where the wood was hung to cure in the heat. “Every month, they would move the wood over one rack.” After two years, the wood would make it to the end of the line, and was deemed sufficiently seasoned for use in a Heintzman piano.

“Out of all the Heintzmans I’ve ever worked on in my 40 years, I’ve seen maybe one with a bad pin block,” Musselwhite says. “They could literally stick it on a dog sled and drive it to the Yukon.” At their peak, Musselwhite says Heintzman made some of the best pianos in the world, particularly the uprights. “It’s the workhorse of the musical battlefield,” he says.

The number of companies that hung on to the 20th-century were much fewer in number, but focused on the names associated with high-quality instruments — Heintzman, Mason & Risch, Mendelssohn Piano Co., Newcombe Piano Co., Nordheimer, and Gourlay, Winter & Leeming, all in Toronto.

Nordheimer also produced quality pianos. “Their grands were fantastic,” says James Musselwhite, calling them a rival to Steinway in the early 20th-century, until about 1920. However, the small Canadian company couldn’t compete with its much larger European rival in the end. “They’re rare — partly because people don’t know what they’ve got.”

Two of the city’s prominent piano makers actually began as one company in a partnership between Thomas G. Mason, Vincent Risch and Octavius Newcombe in 1871. The initial company was a piano retailer selling instruments imported from the United States. However, they began building their own pianos under the name Mason, Risch & Newcombe in 1877. The Canadian Piano Museum has a very rare Mason & Risch & Newcombe piano, built by a company that existed for only one year.

In 1878, the company split, and Mason & Risch was formed. The Mason & Risch piano company’s motto was “Great Is The Privilege Of Achievement”. One of the country’s earliest piano companies, Toronto-based M&R grew to become the country’s largest. The early upright Mason & Risch pianos, built up to the 1920s, are still prized as some of the best ever made. The brand was known for its fine cabinetry work as well as the instruments themselves, and included features typically reserved for grand pianos. Their grand pianos retained their quality till mid-century and are often still worth preserving rather than trashing. In 1900, Mason & Risch formed a partnership with Eaton’s Department Stores and built pianos under the T. Eaton brand for a time.

By 1949, the company had been sold to a subsidiary of the American giant Aeolian Mfg., and the quality declined steadily, leading piano techs to dub the brand “Mason & Risk”. The brand was discontinued in 1972.

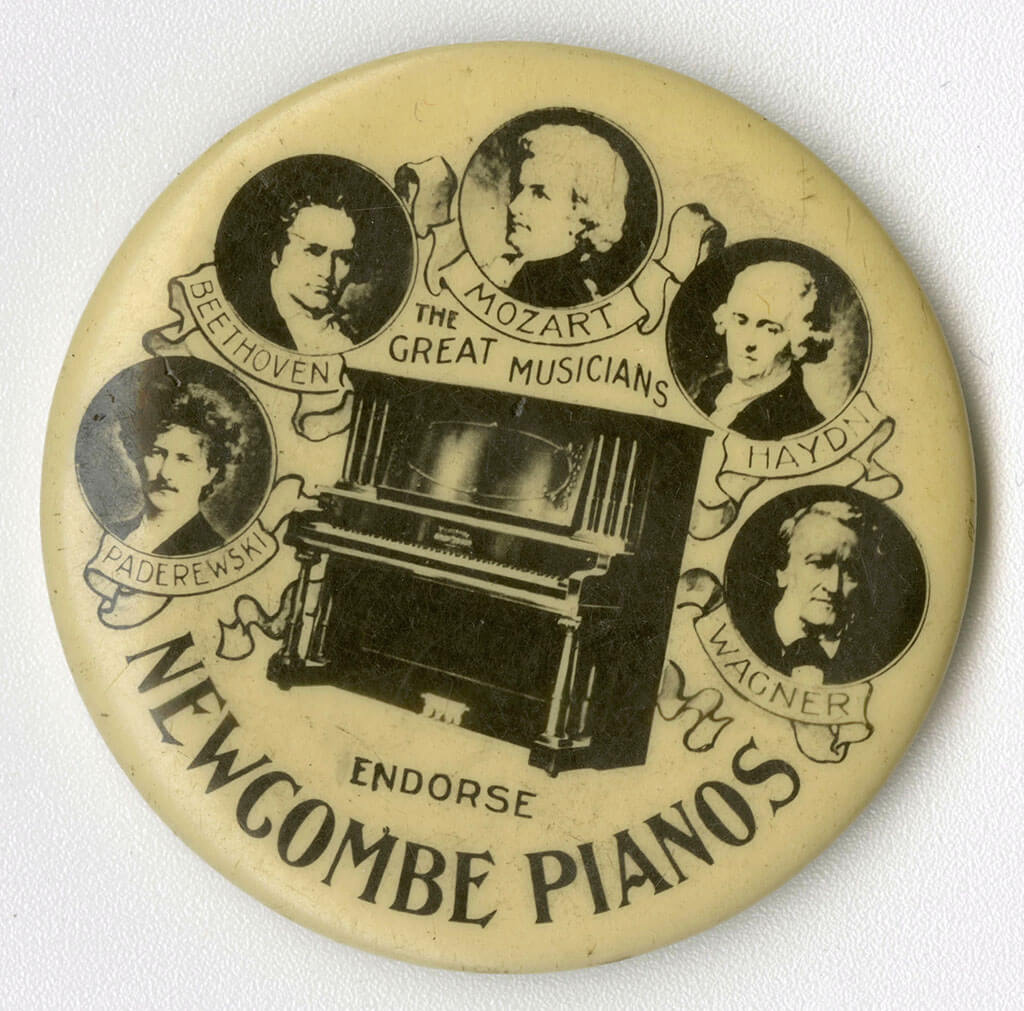

The Octavius Newcombe Piano Company also formed in 1878, renamed The Newcombe Piano Company in 1900. The company became well known for its high-quality uprights and grand pianos that were shipped all over the continent. As the story goes, Queen Victoria asked Sir Arthur Sullivan to find her a nice piano, perhaps one from the colonies. Sir Sullivan chose a Newcombe grand piano built in 1888 or so, and according to anecdotal evidence, it is still owned by the royal family. Unfortunately, the Newcombe factory burned in 1926, and with the market already beginning to fail, it was never rebuilt. The name was later bought by Willis & Company of Montreal, and produced pianos under the Newcombe name until the 1960s.

The market was already in trouble by the early 1920s due to market saturation. “You sell a piano to somebody and it lasts a lifetime,” Lawrie notes. You don’t get to sell them another, in other words.

Gourlay, Winter & Leeming was one of the companies that didn’t survive the first downturn of the market. The company was in production from 1904 to 1923, but quickly developed a reputation for quality and durability, and many still hold up today as candidates for restoration. Cecilian Piano Company was one of many others that got in early and left the business by the early 1920s, having been in operation from 1883 to 1922.

Then came the market crash of 1929. “Most piano factories didn’t survive the Depression,” Hall says. That came despite efforts to adapt to the new reality – smaller households and less disposable income. “These piano factories were amazingly cooperative with each other,” Hall says, noting their often innovative designs. Among the displays at the Canadian Piano Museum are a Toronto-made Mason & Risch upright. “The keyboard fold up into the piano, making it easier to move,” he explains.

The early Heintzman uprights are considered among the best ever made. The quality deteriorated into the 1930s however, as piano makers necessarily built smaller instruments for a depressed market. “A smaller piano is not a good compromise,” says Thomas Lawrie, pointing out that longer strings mean better sound.

From the 1930s to the 1980s, the quality of pianos went down in Canada as well as in the market overall, with some exceptions. Heintzman grand pianos, for example, retained their good reputation well into the 1970s.

The Canadian Piano Museum displays a Mason & Risch dating back to 1938, one of the first drop action spinets in a Swedish design that was licensed to the Canadian firm. “They were struggling through the 1930s to make a smaller piano,” Hall says. “They didn’t sell many.” Before long came the Second World War, and all the factories were put into the service of the war effort. “I think Sherlock Manning made wooden propellers,” Hall notes. Piano output dwindled to virtually nil during the war years. It meant that for a few decades, musicians coveted older instruments and there was a demand for refurbishing.

The post-War boom brought home soldiers and the middle-class consumer. But, while many big-ticket items like cars and washing machines were on everyone’s list, somehow the household piano fell by the wayside. Innovation led to the apartment-sized piano, and a modest boost in sales in the 1950s from an unexpected source — I Love Lucy. The opening sequence for the weekly TV show that turned Lucille Ball into a household name featured an apartment-sized piano in the background. According to Hall, the living room set with its smaller piano brought renewed consumer interest.

The next revolution shook the market for good. “Along came Yamaha in the 1960s,” Hall says. Yamaha, Kawai, and other Asian manufacturers didn’t just come with competing instruments, they came with a whole new automated manufacturing process that would soon rival the quality of the old style piano makers at a fraction of the cost.

“Nowadays the Chinese make pianos that are pretty good,” Lawrie notes.

It was the final nail in the coffin. “They were all gone by 1986,” Hall states. “The last Toronto company was Mason & Risch.” By the 1990s, Canada’s piano making era was officially at an end. Lesage closed operations in 1987, followed by Sherlock-Manning in 1991.

Toronto’s piano sellers are often closely linked to its old piano makers. In 1962, Heintzman opened a second factory in Hanover, Ontario. In 1978, after a merger with Sherlock-Manning Piano Co., the company closed the Toronto factory and moved all their operations to the western Ontario location. Five of its laid-off piano techs found a new professional home at the city’s Robert Lowrey Pianos.

Paul Hahn & Co., a piano tuning and restoration company, was founded by a German immigrant to Canada, a cellist who ended up working for the Nordheimer Piano Company from 1892 to 1913. Today, the company that still bears his name has a stated mandate of sourcing Heintzmans from the classic era and restoring worthy candidates.

Built to last, even at a century old or close to it, there are still many Toronto-built pianos around town, and even beyond. “Canadian pianos from Ontario were being exported all over the Commonwealth. You’ll still find them in Australia – even the UK.” Thomas Lawrie notes.

“There are lots still around,” says James Musselwhite. “A lot of the pianos that were made in the early 20th-century — there’s very little demand for them. Sadly, quite often they go to the dump. We try to encourage people to restore older pianos.” The price, however, is often prohibitive and can range to $15,000 or more. Sometimes, the restoration is more than the piano could ever possibly be worth. Companies like Paul Hahn & Co. often have old Heintzmans or other Canadian pianos in stock, but they can be a hard sell. “They don’t sell like Steinway,” he says. “There’s not a big demand.”

“There’s a lot of basements,” Thomas Lawrie, a piano technician based in the Niagara area, echoes. “There’s not a lot of market value. A piano has a complex mechanism that wears out.”

“People are sending them to the dump and selling them on Kijiji,” Halls says. “It’s depressing.”

About that crystal Heintzman grand piano…Heintzman Ltd. was sold to Sklar-Pepplar Inc., a furniture manufacturer, in 1981, and predictably, produced pianos that were more furniture than musical instruments. They ceased operations in 1986. The name was sold to The Music Stand, an Oakville based retailer who tried to relabel and sell foreign-built pianos under the Heintzman name. That was stopped by a court action initiated by the Heintzman family.

In 1989, a partnership of the Beijing HsingHai Piano Group and Canadian investors created the company that is today still known as Heintzman Piano Company, often called Beijing Heintzman. The Toronto component still lives in the manufacturing equipment, toolings, and scale designs that were brought over from the Canadian factory to China along with the Canadian plant manager to oversee the manufacturing operations.

John Hall recounts how, in 2000, he was astounded to discover a Heintzman booth at a piano convention in Las Vegas. The booth bore the logo of a company called Beijing Heintzman. “Their product improved tremendously,” Hall says. While most sales are concentrated in Asia, you can find those new Chinese made Heintzmans in North America if you look hard enough. “There are a few dealers,” he notes.

According to the most recent reports, the company today is controlled by majority Canadian shareholders, and the plant still uses Canadian soundboards manufactured by Les Pianos André Bolduc Inc. in their top of the line grand pianos. The company’s motto is, “The Canadian legend continues in China”.

A quirky twist of globalism, perhaps. But, the name lives on.

Fun fact: A remnant of Toronto’s Golden Era of the piano still exists in the west end in Heintzman Avenue, a small street just east of The Junction. Near where a Canadian Tire now stands, the old factory once stood.

- PREVIEW | Cellist Elinor Frey And London Symphonia Dive Into Jewels Of 18th Repertoire - April 25, 2024

- PREVIEW | The Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra Says Good-Bye To Conductor Gemma New With Music - April 25, 2024

- THE SCOOP | Not-For-Profit Euterpe: Music Is The Key Received Three-Year Grow Grant - April 24, 2024