Parsifal: Richard Wagner (composer), Jonas Kaufmann (Parsifal), Nina Stemme (Kundry), Christian Gerhaher (Amfortas), Rene Pape (Gurnemanz), Wolfgang Koch (Klingsor), Balint Szabo (Titurel); Kirill Petrenko, conductor; Georg Baselitz, designer; Bayerisches Staatsorchester. National-theater, July 5, 2018.

MUNICH — To Wagner opera fans, the 2018 Munich Opera Festival holds many highlights, but perhaps the main attraction is a new production of Parsifal, designed by noted German painter Georg Baselitz and directed by Pierre Audi. It opened the Festival on June 28 for a run of five performances, including the closing night on July 31.

As is typical with concept productions, this Parsifal opened on June 28 to divided opinions. Based on reports from colleagues, there was vociferous applause from the audience towards the singers and conductor Kirill Petrenko, while the creative team was greeted with cheers and some loud booing from a few, directed at Georg Baselitz. Opinions in the press were equally divided, ranging from a highly positive critique by Rupert Christiansen in the Telegraph to a much less favourable one by Zachary Woolfe in the New York Times.

I caught the third performance, on July 5. Having attended the Festival for ten consecutive years, I can say that Munich and Bayreuth have the ‘model’ Wagner audience — knowledgeable, quiet, attentive, and discerning. For five and a half hours in a packed, non-air-conditioned house and with many dressed to the nines, they exhibited unflagging discipline, with no fidgeting, and so quiet you could hear a pin drop. Rather than summarizing the story here, I’ll instead share my thoughts on the production and the musical sides of things.

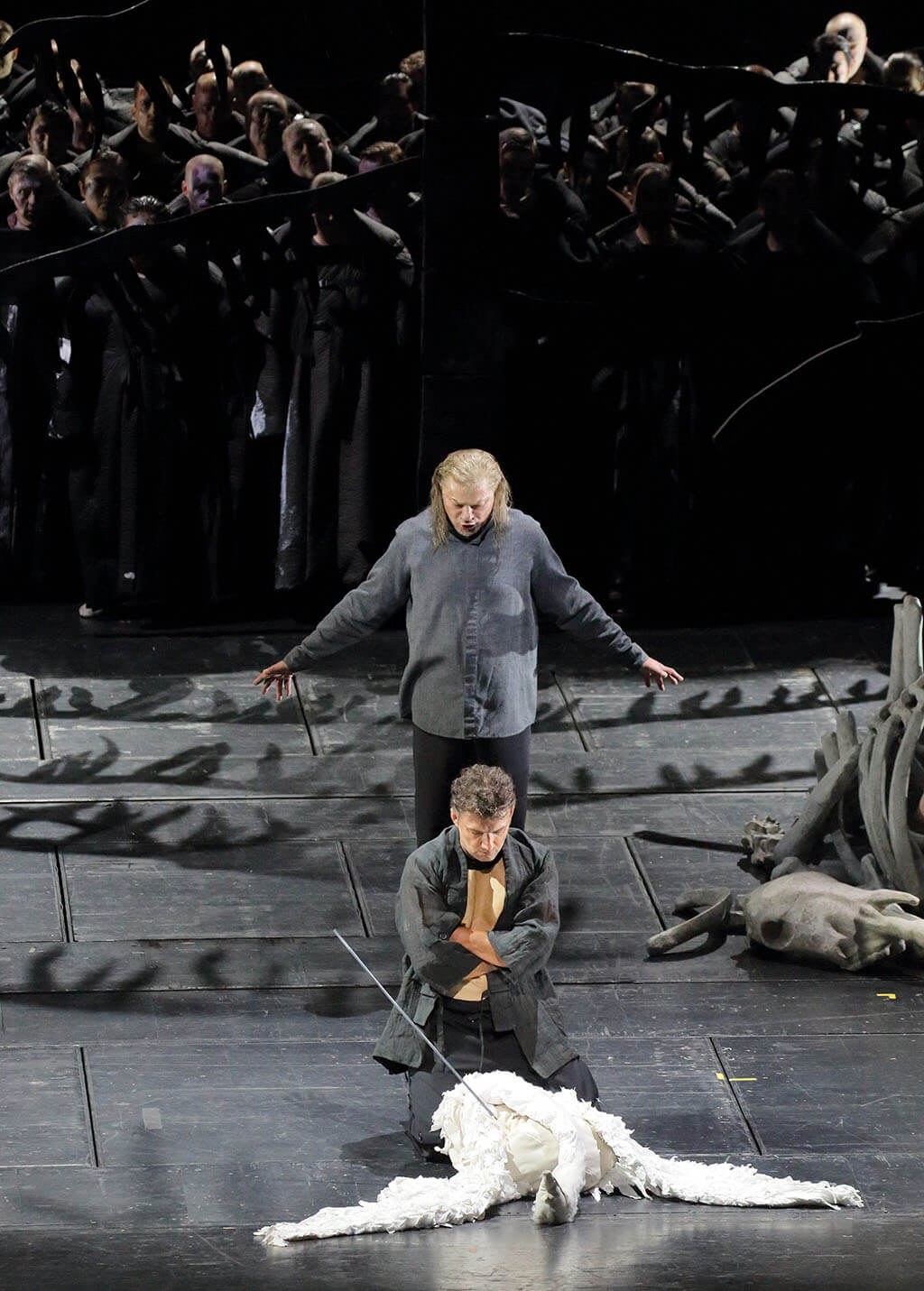

As expected, the mis-en-scene is modern, based on Baselitz’s black and white paintings of aged and decrepit naked bodies. Act One is essentially naturalism with a twist – after the Communion, the trees begin to sink, eventually collapsing to the ground. While it does create a striking effect, its meaning remains elusive. There’s a surprising absence of religious symbolism — no Grail and no Crucifix unless you count the feeble-looking cross Klingsor uses as a spear. Kundry’s dwelling is under a horse’s skeleton. Poor Amfortas, supposedly suffering unbearable pain from his bleeding wound — he is made to wander around the stage with a cane.

In the more typically “operatic” Act 2, Klingsor and Kundry make their entries by crawling out from under a roughly painted curtain that resembles a stone wall of sorts. Unlike the wild woman in Act One, Kundry is blond and all dolled up, not out of place as a diva giving a Liederabend. Perhaps the most distracting touch in this production is the costuming for the chorus, where most have on flabby naked body suits. The knights are not shy to take it all off during the Communion. Klingsor wears enormous black shoulder pads and has an exposed belly button. In Act 3, the trees and the hearth are upside down, hanging from the ceiling. Also in the last act, Parsifal wears an enormous codpiece.

I mention these seemingly random and disparate points not to be nitpicky. Baselitz and Audi are obviously making a statement, but I’m struggling to understand their vision. There’s a short, two-part trailer put out by Munich Opera where Baselitz, Audi and the principals speak briefly, but it’s sadly not all that illuminating. As I see it, the emphasis of the ugliness of the body is an attempt to underscore the eternal struggle between the spirit and the flesh that is the one of the central themes of this opera. That said, it seems inconsistent that the religious symbolism is deemphasized, and the Flowermaidens, whose purpose is to seduce Parsifal, are equally decrepit-looking.

As to Parsifal’s wearing of the codpiece in Act 3 — I give the disciplined audience full marks as there was not a single giggle to be heard. My reading of that is he has gone from the simple fool in Act 1 to that of a mensch in Act 3, and sexuality is part and parcel of manhood. The production is dimly lit and visually unattractive. Before I get called out for favouring prettiness, I do feel that while beauty should never be a given in opera, it should reflect the situation when it’s called for, such as in the Blumenmadchen scene. I find all these peculiarities distracting, and interferes with the sublime moments in the music, such as the transformation scene in Act 1 and the Good Friday music later.

As is quite often these days with concept productions, the one unalloyed pleasure is invariably musical. Top honours go to tenor Jonas Kaufmann, who sounded wonderful as Parsifal, although I would like a bit more youthful and playful manner in Act 1 and with the Flowermaidens in Act 2. Soprano Nina Stemme was an impressive Kundry; her dark timbre suits the character well. She also sang a caressingly beautiful “Ich sah das Kind” and had all the Bs and B-flats for the climaxes, though she telegraphed each high note with obvious preparation!

Rene Pape was as expected a very fine Gurnemanz, who has more to sing than anyone else in this opera. As Amfortas, Christian Gerhaher sang with power and beauty of tone, not to mention Lieder-like intensity. Wolfgang Koch was a properly evil Klingsor and made to look ridiculous by his costume. But given this character, I suppose it’s par for the course. All the smaller roles are exceptionally well cast — First Blumenmadchen was Golda Schultz, no less! Kirill Petrenko conducted flawlessly, with great power and delicacy. The torrents of sounds from the pit were truly thrilling. The sounds from the Monsalvat Bell leitmotif in Act 1 was overwhelming — I even felt the vibration coming from the floor and up my legs!

As a regular visitor to European opera houses, I have seen my share of Regie-driven productions. Take Munich as an example – some I like very much, such as Calixto Beieto’s La Juive, while others I find deeply flawed, such as its Pelleas et Melisande, which to my knowledge has yet to be revived. While I’m in favour of periodic rethinking of the standard repertoire to reflect current sensibilities, it must be done in such a way that is respectful of the composer’s intentions. And that means without changing the text, the drama, or the music in a major way. The Baselitz-Audi Parsifal does not betray the spirit of the work, which is commendable. But in my mind, the director’s vision isn’t clear to the audience. The quirkiness can only result in an overall weakening and thus a loss of impact of the work on the audience.

I could go on, but I won’t. And you don’t have to take my word for it, as the performance on July 8 will be live streamed from the Max-Josef-Platz just outside the National-theater. You can watch it and decide for yourself. It starts Sunday at 5 p.m. Munich time/noon in Toronto. Rest up for the marathon!