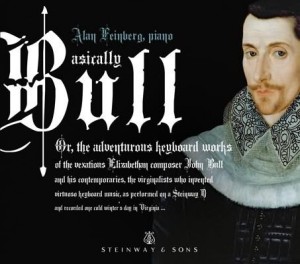

Some albums live up to as well as contradict their titles. One remarkable find from last week’s releases is Basically Bull, Or the adventurous keyboard works of the vexatious Elizabethan composer John Bull, and his contemporaries, the virginalists who invented virtuoso keyboard music, as performed on a Steinway D and recorded one cold winter’s day in Virginia…

Some albums live up to as well as contradict their titles. One remarkable find from last week’s releases is Basically Bull, Or the adventurous keyboard works of the vexatious Elizabethan composer John Bull, and his contemporaries, the virginalists who invented virtuoso keyboard music, as performed on a Steinway D and recorded one cold winter’s day in Virginia…

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

This release on the relatively new Steinway & Sons label was recorded by veteran New York City pianist Alan Feinberg, who has made a career of championing the adventurous and obscure — be they of today or the past.

Historical purists will likely frown because Feinberg has harnessed a big, bold modern concert grand piano to perform a task the composer reserved for for the tiny, dainty-sounding, virginal — a lady’s instrument of choice in any well-appointed turn-of-the-17th century English drawing room.

This is Basically Bull. Here is fine music sensitively translated into what is essentially a completely different idiom while still preserving its essential character (a strange and wonderful mix of polyphonic and contrapuntal writing) while making it easy on the modern ear.

Bull (1562/3-1628), along with Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625) and William Byrd (1540-1623), were the three English keyboard pioneers, collecting their groundbreaking little pieces for the virginal into the first published collection of keyboard works, Parthenia, or the Maydenhead of the first musicke that ever was printed for the Virginalls, in 1613.

(The saucy lads named their sequel volume of 1614 Parthenia In-Violata, adding parts for bass viol.)

Besides being a cad chased from England’s shores for his adulterous behaviour, John Bull’s distinction in this great triumvirate is of being the crazy virtuoso, writing in technical demands that no dainty Saturday-night player can hope to master. I think the modern piano actually improves this music, removing the tinkly sound that gets pretty raucous when there are three or four voices moving quickly along the keyboard at the same time.

Also Basically Bull dispels any notion that harmonic and rhythmic invention is a thing of the present. There are examples in any age, going back to Medieval times, and Feinberg has picked some fine examples from circa 1613. The pianist has also included some gems by Bull’s contemporaries, including one of Gibbons’ exquisite Fantasias.

There are 20 pieces in total on the album, each representing a different aspect of the keyboard art of the early 17th century — and all oriented toward making everything sound as musically alluring as possible.

In short, this album is Basically Excellent, not Basically Bull. It could serve as a fine entry into a whole new musical aesthetic for someone not naturally drawn to pieces from this period.

You’ll find all the details on the album here.

I wish there was something of Feinberg’s work from this era available on YouTube. Instead, here are others to entice, starting with a visual take on on Bull’s In Nomine XII (not on the album), followed by Michael Maxwell Steer playing the harpsichord for another In Nomine divided into measures of 11 beats, and young American pianist Aaron Tan playing a Gibbons Fantasia:

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019