Any serious musician will tell you that a fine interpretation depends on knowing as much as possible about a composer’s life and the story behind a particular piece of music. But what do you do when the music has survived, but its backstory has disappeared?

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

Send out the scholars, and speculate.

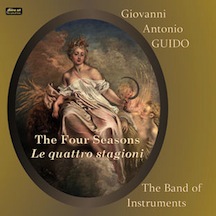

The Band of Instruments, resident at Oxford University for nearly 20 years, recorded The Four Seasons back in 2004. Not Vivaldi’s omnipresent concertos, but a set written by Italian composer Giovanni Antonio Guido around more or less the same time.

The album has just been reissued by the Divine Art label. I stuck the CD into the slot and was really impressed by the richness and inventiveness of these concertos (and perhaps a bit less impressed by the Band’s very competent, technically stellar but also slightly colourless playing).

The album has just been reissued by the Divine Art label. I stuck the CD into the slot and was really impressed by the richness and inventiveness of these concertos (and perhaps a bit less impressed by the Band’s very competent, technically stellar but also slightly colourless playing).

Each of the four concertos — Guido entitled them Scherzi armonici sopra le quattro stagioni quell’anno (Musical diversions on the four seasons of the year) — is written in French suite style rather than the Italian fast-slow-fast succession of movements.

Each movement comes with a descriptive label.

In the second concerto, Summer, the opening is marked “L’air s’enflame, Spirituoso” (The air catches fire, Quickly), followed by Zephire diaparoit, Adagio e piano (Zephyr vanishes, slowly and quietly). It’s followed by a beautiful cuckoo song.

For those of us who stood on the brink of depression over our lingering winter this year, Guido would have offered a salve in the final movement of Winter: “Laissons gronder les vents — Banissons la tristesse, Presto” (Let the winds howl — Banish melancholy, Quickly).

Is the music as arresting as Vivaldi’s? No. But it’s not for lack of invention and originality, or vituosity. I suspect what weighs against Guido’s pieces is the shortness of each movement; it’s gone just as it is beginning to develop nicely.

The musical themes, harmonies and counterpoints are all geared for maximum descriptive effect with a minimum number of notes. But sometimes it’s good to develop ideas a bit more.

Even so, the music is beautiful enough that I was reminded of the flip side of the know-the-background equation: Where a musician uses knowledge to improve their performance, the listener seeks knowledge to deepen their appreciation.

I didn’t know anything about Guido, nor does anyone else. Even Wikipedia, which thinks it knows things even scholars don’t, can only manage a paragraph on the composer on its Italian site.

Fortunately, Michael Burden has written fascinating notes for the album reissue that are a showcase of the musical sleuth’s art, connecting disparate dots buried in lists and letters to trace Guido’s journey from Naples, where he might have been born around 1675, to the court of the Duc d’Orléans (nephew of King Louis XIV and future ruler of France until the Dauphin, Louis XV, was old enough to assume the throne) in 1698.

Guido brought the Italian style to the French court. It also looks like there’s a convincing case that Guido’s Four Seasons pre-date Vivaldi’s — as does his use of poetry to illustrate each time of year. Scholarship suggests that Guido’s pieces date from 1716-1717 and may have been written to celebrate the unveiling of four oval paintings by Watteau depicting the seasons in the Paris home of wealthy and well-connected businessman Jean-Pierre Crozat.

And it’s thanks to Watteau’s sketchbook that the world has the only known likeness of Guido, shown above (which I scanned from the back of the CD booklet).

Ultimately, none of this matters, because the music stands on its own. But, as Tafelmusik has shown with its curated multimedia programmes, historical details and coincidences add a whole other layer of interest.

Tafelmusik bassist Alison Mackay, who has been the mastermind of so many of these programmes, is behind the Toronto Consort’s season-closing concerts at the end of May, which celebrate pre-18th century women composers. Here, as in Guido’s story, we get a peek at fascinating tidbits kicked into the shadows by the passage of time (details here).

If your interest in Guido has been piqued, you’ll find more details about the album along with a short audio excerpt from Summer here.

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019