Renaissance choral composers wrote for vast, reverberant spaces. Bach wrote his harpsichord pieces for small rooms that wouldn’t smudge the intricate counterpoint. In the same way, a performer needs to adapt their playing style to the place where people are going to hear it.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

The practical side of acoustics is something we instinctively react to, but seldom think about.

The Banff Centre has produced a wonderful, 10-minute podcast, “These rooms are instruments,” that illustrates how space affect and inspires composers, performers and audiences, that is well worth hearing:

+++

The podcast helped me remember how hearing my little voice fill a very large space for the first time had me walking on air for a long time afterward, and how important it is to get children out of the dry acoustic of a classroom and out into a space where they can experience the wonder of natural amplification.

It is the road to musical epiphanies.

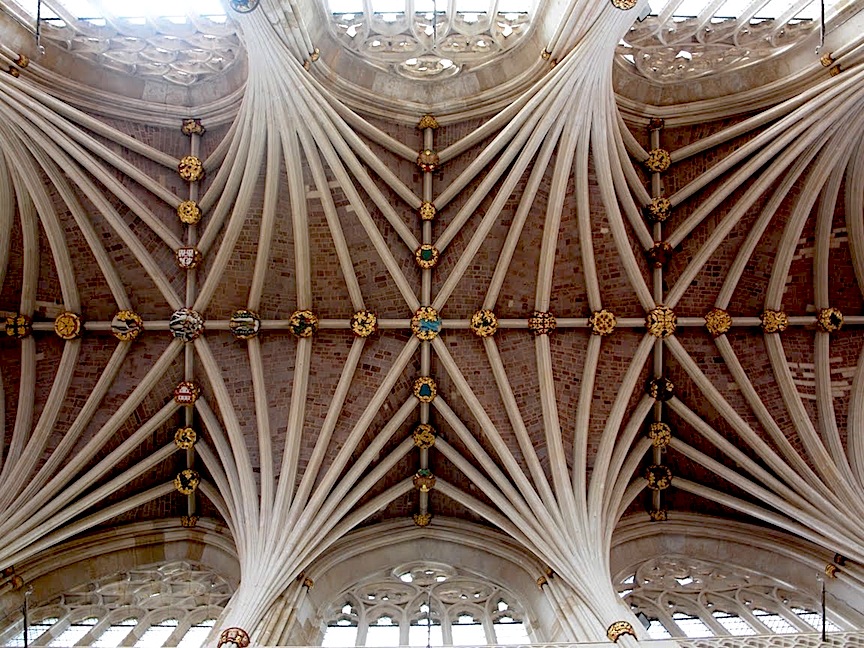

Here is a setting of the Te Deum by English composer John Ireland (1879-1962) written to sound its best in an acoustic like the one we hear around the choir of Lincoln Cathedral, led by Colin Walsh (the organist is Andrew Post):

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019