It’s crazy how some insults stick, even when there isn’t a shred of truth to them. German critic Oscar Schmitz in 1904 declared Britain as “das Land ohne Musik” — the country without music. It’s so crazily untrue that you would think it not worth responding to, except that these words weren’t forgotten.

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019

There was a long list of great composers writing excellent music in late-Victorian and Edwardian times — really the apogee of mass concerts — from Granville Bantock (1868-1946), who, among other things, helped revive Elizabethan music for his times, to Edward Elgar (1857-1934), Gustav Holst (1874-1934), Irish-born Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) and Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958).

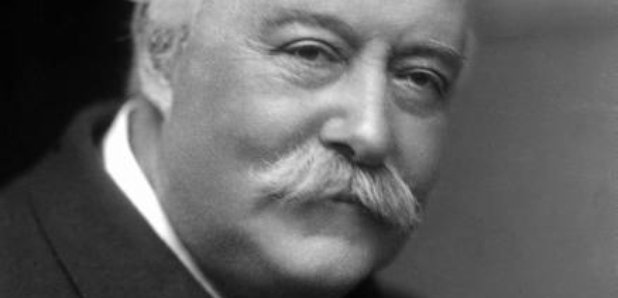

Because he was a notable scholar and teacher, Hubert Parry (often written as C.H.H. Parry, for Charles Hubert Hastings) had an influence that reached well into the 20th century. His music is gorgeously crafted, if not adventurous.

After finally wrestling his father’s wish to have him earn an honest living in business to the ground, Parry completed his musical education and began to teach at the Royal College of Music in London in 1883, at age 35. He served as director of the school from 1894 until his death in the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918.

He wrote music for all genres, including an opera (Guinevere) that was never produced. He also wrote four music-history books including, in 1909, a study of J.S. Bach.

Because Parry worked on elaborating his ideas using traditional means, he was ridiculed in his day. In a book on Parry, Michael Allis mentioned how the ever-ascerbic George Bernard Shaw summed him up as “a conservative, out-of-touch pedant.” In his survey of Romantic-era British music, Bristol University scholar Stephen Banfield wrote: “Parry’s naturally liberal imagination was thwarted and all too often crushed, in his prose as in his compositions, by a sterile aristocratic lineage.”

Not much to celebrate, then?

Parry’s most enduring hit is “Jerusalem,” which is sung so often that it would probably become the anthem of an English republic. Here it is from the most recent Last Night of the Proms, courtesy of the BBC Symphony and conductor Jiri Belohlávec:

But it’s not fair to use republican and Parry in the same sentence. He wrote one of the great coronation anthems in 1902, the Psalm setting, “I was Glad.” Elizabeth II used it in 1952, and it was the processional at the most recent royal wedding. Here’s a a more intimate, imperfect, student performance from the choir of Somerville College, Oxford, also from last summer, with organ scholar Robert Smith:

Because it’s winter and some of us might want to spend a bit more time indoors, I thought, why not listen some more and come to our own conclusions.

Here is one of Parry’s organ pieces, a Prelude on The Old 104th. The title refers to the name of an old hymn tune that the organist — W. Leigh Fleury at the console of his home church, Westminster Presbyterian in Clinton, SC — plays with his feet:

Parry completed his Symphony No. 2 in 1883 and revised it substantially a few years later. It has four movements and a cyclical stucture, meaning that key musical themes return throughout the piece. The third movement Andante (which starts right after the 19-minute mark) is the finest, I think.

The symphony is subtitled “Cambridge,” but that has to do with where it had its premiere, not with any other meaning or depiction. It’s performed here by conductor Matthias Bamert and the London Philharmonic Orchestra:

Here, for chamber-music lovers, is Parry’s Piano trio No. 2, in the ever-dramatic key of B minor, from 1884. It is played by the Deakin Trio — violinist Richard Deakin, cellist Emma Ferrand and pianist Catherine Dubois. There are four movements here, too, with the slow movement coming second.

Give the piece a couple of minutes to get over the ponderous Maestoso opening section, and the honey starts to flow:

For me, the most special Parry can be found in his a cappella Songs of Farewell, motets that have long kept me good company. Here is “My Soul, There is a Country,” sung by the choir of Exeter College, Oxford inside the echoey Madeleine church in Paris.

The text is a setting of “Peace,” a 17th century poem by Henry Vaughan:

My soul, there is a country

Far beyond the stars,

Where stands a wingèd sentry

All skilful in the wars:

There, above noise and danger,

Sweet Peace sits crown’d with smiles,

And One born in a manger

Commands the beauteous files.

He is thy gracious Friend,

And—O my soul, awake!—

Did in pure love descend

To die here for thy sake.

If thou canst get but thither,

There grows the flower of Peace,

The Rose that cannot wither,

Thy fortress, and thy ease.

Leave then thy foolish ranges;

For none can thee secure

But One who never changes—

Thy God, thy life, thy cure.

John Terauds

- Classical Music 101: What Does A Conductor Do? - June 17, 2019

- Classical Music 101 | What Does Period Instrument Mean? - May 6, 2019

- CLASSICAL MUSIC 101 | What Does It Mean To Be In Tune? - April 23, 2019