Brahms used it to exorcise himself of his failed loves, while many composers simply spelled out their own names. They represent examples of what is called musical cryptography or a music cryptogram.

Musical cryptography is the use of music to encode messages. In its simplest form, the letters A through G can be used to spell out words or codes.

Most students of classical music are familiar with the B-A-C-H sequence to be found in J.S. Bach’s work. H is the equivalent of a B-natural in the German system of music cryptography, allowing Bach to spell out his name quite easily. It’s a motif that he incorporated into several pieces, including The Art of the Fugue. While Bach is perhaps its most famous user, music cryptography was fairly common, largely in the Classical and Romantic periods.

Music cryptography had its proponents in the 17th- and 18th-century, chiefly mathematicians. Composer Michael Haydn, brother of Franz Josef, allegedly proposed a musical cipher system that was published in a biography of his brother in 1808. In his system, the alphabet begins at the G on the bass clef as A, then G-sharp as B, and so on.

Knowing a little about the life of Johannes Brahms makes it easy to believe he might choose musical cryptography as a way of expressing himself.

Famously, Brahms and Clara Schumann fell in love, and Clara was finally free to pursue a relationship with him after the decline and tragic death of husband Robert at 46. But, Brahms kept his distance, and made it clear that, despite his feelings for her, he would never marry her.

Their relationship was over by 1856, just before he met Agathe von Siebold, his second great love. Agathe was a soprano who was taking lessons from his friend Julius Otto Grimm. Clara actually caught the two of them canoodling in September 1858. “He left me alone with words of love and devotion, and now he falls for this girl because she has a pretty voice,” she complained in a letter.

However, even though Brahms proposed marriage at first, the relationship was doomed after his Piano Concerto No.1 D minor tanked at its premiere. He was worried about being able to provide for a wife, and called the wedding off in January 1859.

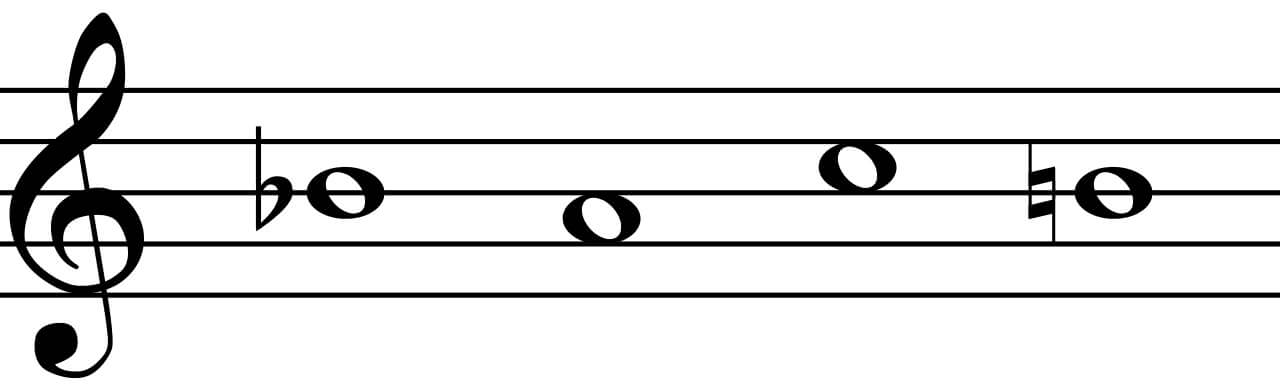

In the summer of 1864, Brahms heard that Agathe had left Germany for Ireland to work as a governess. His next composition, already in progress, was his String Sextet No. 2 in G major. In the climax of the first movement, bars 162 to 168, he refers to his lost love with a theme that goes A-G-A-H-E.

In a different sort of cipher, he also incorporated a melody that he had first written in a letter to Clara Schumann years earlier. The theme opens the first movement, and is present throughout the composition. Brahms wrote about the composition in a letter to his friend Josef Gänsbacher, “by this work, I have freed myself of my last love.”

Agathe later wrote about the relationship in a novel. She eventually married and by all accounts happily, although she always admitted to carrying a torch for Johannes, while for Brahms, love remained something idealized but not lived. Though he remained unmarried, Brahms retained his penchant for musical codes, referring to Adele Strauss by the notes A–Eb (A.S.) and to Gisela von Arnim, a writer known for her fairy tales, with the notes G#–E–A (Gis-e-la) in his letters.

Brahms: String Sextet No. 2, Op. 36; Harriet Krijgh & Friends — Live HD

There are also many examples of musical cryptography outside the world of classical music composers. The earliest known reference to the practice comes from a late 15th-century manuscript titled Rules for Carrying on a Secret Correspondence by Cipher, currently in a collection at the British Library.

The first time the New York City Police Department successfully intercepted and interpreted a secret message in code, it was a melody on a treble clef being used by local bookmakers to keep track of illegal bets.

There are many rumours and stories about musical cryptography being used for spies, notably during the Jacobite Rising of 1745 in Scotland. Various schemes and purposes have been proposed, even in multiple academic papers, but there is no confirmed case of using musical cryptography for spying or other secretive purposes in modern times.

However, it is also known that candidates for the crypto-analysis service in the British army during WWII were asked if they could read an orchestral score.

The practice appears in books and TV. In Outlander, the romantic time travel drama set in 18th-century time Scotland, our heroes Jamie and Claire decipher the code in a piece of German sheet music that uses key changes in Bach’s Goldberg Variations to transmit the message. Author Stefanie Pintoff also uses the ruse in her novel Secret of the White Rose.

Schumann, Carnaval, op. 9 by Boris Giltburg

Music cryptograms weren’t always used for such dramatic or significant reasons. A diverse list of composers that includes Liszt, Rimsky-Korsakov, Busoni, Beethoven, Ravel, Debussy, Poulenc, Elgar and Shostakovich have used music cryptography to simply spell out their own names within their works.

Olivier Messiaen created a code that used different notes to spell out all 26 letters of the alphabet. In his work for organ, Méditations sur le mystère de la Sainte Trinité, the complex web of tones and rhythms spells out French words from the work Summa Theologica by philosopher Thomas Aquinas.

Irish composer John Field composed melodies encrypting the words B–E–E–F and C-A-B-B-A-G–E as a tribute to a generous hostess, while Glazunov wrote a theme based on the name of his dog, S–A–C–H–A.

Often, composers marked an obvious tribute to another composer with a musical cryptogram, such as Ravel, who wrote Menuet sur le nom d’Haydn for piano in 1909. In 1929, Poulenc, Honegger, Milhaud, Ibert and others got together to commemorate Albert Roussel in their works.

Brahms’ friend Robert Schumann was also known to use cryptography in his compositions. In his Carnaval Op. 9 for solo piano, he includes more than one. A-S-C-H (with S represented by E-flat and A by A-flat in the German system) is a shout-out to his (then) fiancée Ernestine von Fricken’s hometown of Asch, Germany, and the sequence S-C-H-A is just riffs off his name, proving that great composers can be as random as anyone else.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on classical music and opera news and reviews? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter for all the latest.