The chamber music of Frederick Block, the Jewish-Viennese composer you’ve never heard of, is the focus of the eighth Music in Exile release by Toronto’s ARC Ensemble. Music in Exile Vol. 8: Chamber Works by Frederick Block was released in October 2024.

The GRAMMY nominated ARC Ensemble has made the discovery and rehabilitation of the works of composers whose careers were derailed by the Nazi regime and the Second World War its focus.

The concept of “Music in Exile” can take many forms. When it comes to composer Frederick Block, it’s a story of young promise that was squelched when the Nazi annexation of Austria made his life there untenable.

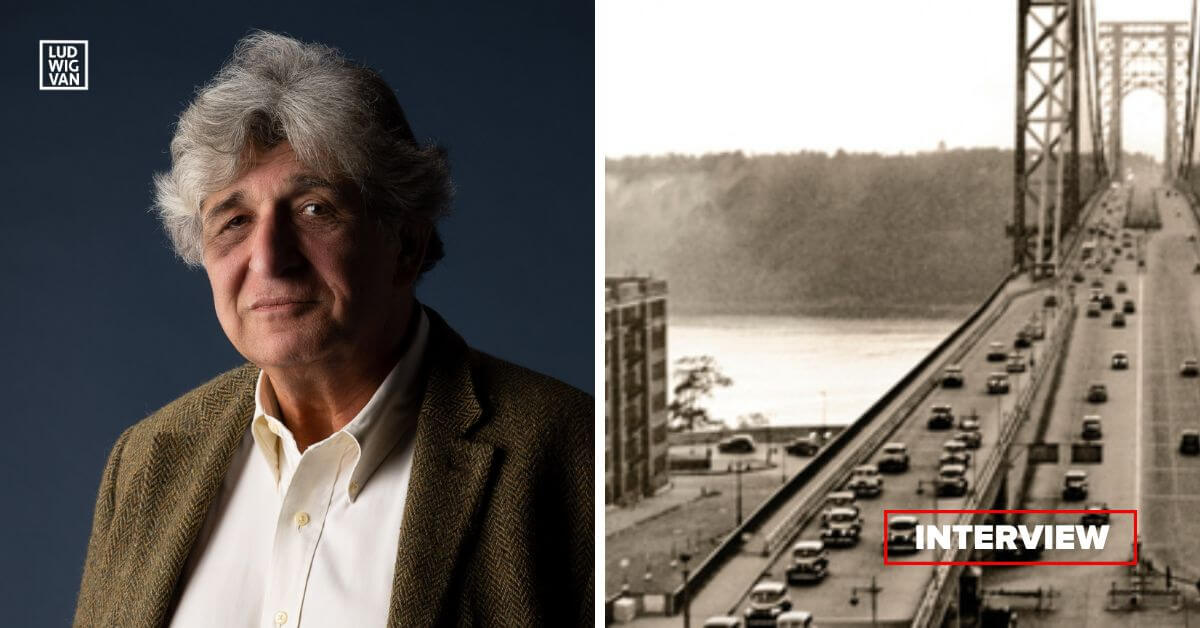

We spoke to ARC’s Artistic Director Simon Wynberg about Block and his music.

Frederick Block

While Wynberg is involved in a constant effort to dig up forgotten scores and artists from that period, most of the time, he has an idea of what he’s looking for. Block, however, was a complete unknown that he wasn’t familiar with at all.

“No, and neither were any of my colleagues,” says Wynberg. “They’d looked him up, after I mentioned him, and they found some contemporary newspaper reports about him.”

Born in 1899 into a wealthy family, Block’s life as a composer wasn’t really typical of his contemporaries.

Frederick began studying piano at the age of nine. His parents actually discouraged him from a career in music, a path that was set aside during his military service in World War I. On his return, he took matters into his own hands, and enrolled at the Vienna Conservatory.

He debut as a composer took place in Vienna in 1922, and it sparked a career that developed gradually. Frederick’s music was broadcast on the radio in Prague and Vienna, and his reputation grew throughout the 1920s and 1930.

Starting out, his work consisted largely of smaller chamber pieces. As his career gained momentum in the 1930s, he turned to orchestral works, and operas, of which he wrote six between 1933 and 1937. He would later write another two, including both music and libretti.

“He was very keen on opera,” Wynberg says.

1936 saw the height of his career as composer when his opera Samum was produced by the Slovak National Opera in Bratislava. One of the performances was broadcast nationally, and the work received a wave of acclaim from both critics and audiences.

“It was 1936, and it looked as if his career was really on an upward trajectory. That opera, in particular, I believe, marked what could have been a fairly significant career.”

By 1938, however, his life was under threat after the Nazi annexation of Austria. Block left for London, where he waited about a year for the paperwork to travel to North America. In the meantime, he met and married his wife.

In June 1940, the couple made the move to New York. Frederick and Ina Block settled in Washington Heights, New York City — then dubbed Frankfurt on the Hudson for its preponderance of German-Jewish emigres. It’s a moniker that endured for about a half century, from 1933 to 1983. It was a welcoming environment, but not necessarily a hotbed of European high culture.

After settling in New York, finding work became his most pressing issue. Block found a way of generating income, but it wasn’t through the orchestral work. He found a well-paid niche creating orchestral arrangements for CBS, along with piano transcriptions of major orchestral works for a music publisher. Block himself didn’t count the arrangements when he kept records of his own composed work.

During his time in New York, he told many people of his premonitions of looming death. It spurred him into setting as many of his works down on paper as possible. In New York, alongside his commercial work, he completed an opera (Esther), three symphonies, four suites, several chamber pieces, along with works for solo piano, and vocal music.

True to his dark visions, Block died in on June 1, 1945.

Falling into obscurity

“He really is locked into the vaults of history.”

Part of that can be ascribed to his roots. With his family background, and a family trust to live on, Block didn’t need to have the public success to survive. He didn’t even have to publish, free to pursue wherever his talents led him.

“He wasn’t really interested in promoting himself,” Simon notes. “You have this curious situation.” Even during his early career years in Vienna, where he was a teacher and musician, few of his works were published. “He wasn’t associated with any conservatory or university.”

On arriving in the US, however, the latter fact would come back to haunt him. He applied for the assistance available for refugee artists from various sources in his new country; however, without the formal credentials and association with an established institution, he found himself competing with PhDs and professors, and shut out of any funding.

“He was a bit miffed about that.” Even as a teacher in Vienna, Wynberg points out, Block would shun the high profile kids with wealthy parents in favour of talented students without parental clout. It left a promising career with a momentum he was just building fizzling out before his eyes.

“One of many people who were sidelined,” Simon notes.

The miracle is that there is anything left to discover at this late date. With most published work done for CBS, and his contemporaries also gone, there was no one left to keep his work alive at that level. That boils down to the wife he met and married in London.

“His wife was extraordinarily supportive of him,” Wynberg says. After Block’s death, she organized a few concerts of his music in New York City in an attempt to perpetuate his legacy. However, while she had supporters, five years or so after his death, he began to sink into obscurity as the classical music world lost interest in what was to them unknown music.

“But his wife kept all of his material,” he explains. On her own death in 2000, all of her belongings, including Frederick’s documents, were passed along to a friend in New Jersey name Cathy. “She was the executor of Ina’s will.”

Cathy donated boxes of Block’s papers, including a treasure trove of unpublished music manuscripts, to the New York Public Library. That’s where Wynberg discovered Block — in a reference to the NYPL’s acquired collection.

However, Cathy discovered a few more music manuscripts, and came across ARC and Simon and their work online. She emailed Wynberg to tell him she had scores from both Block and “other composers”, as she described them (Wynberg’s transcriptions). Then, a month later, she discovered several more boxes of material, including photographs and diaries, that she had also stored and forgotten about. She got back in touch.

“I’m going down next month to have a look,” Wynberg says. While most of the music seems to have found its way to the NYPL system, there may yet be even more music to rediscover.

“The story continues. This hasn’t happened before,” he says. The material has been with her for almost a quarter of a century now, as he points out. “It’s really quite an interesting story.”

Frederick Block, the music

“He was one of many traditionalists,” Wynberg notes.

Block remained unmoved by the sparks of modernism during his era, influenced instead by late 19th century romanticism. “He saw himself as part of a tradition.” That’s not to say his music is bland or rote. “It definitely has its own personality.”

Wynberg describes it as tonal, with influences of Strauss, Korngold, and Mahler, “but with his own stamp,” he adds. “Some of the later works have a slightly different, a slightly more modernistic side to them.” But, that only goes so far. “He had absolutely no time for the serial school. At all. Not interested in Schoenberg. He was very fond of Mahler. It’s sophisticated music,” Wynberg comments.

“There’s no reason why his music shouldn’t be programmed, and programmed regularly,” he says of the quality of the work. “We’re the first to explore this repertoire, but there’s a lot of it,” he says, noting that his hope is someone will discover and present Block’s large body of vocal and opera music.

“There’s a large body of work yet to be explored.”

- The CD Music in Exile Vol. 8: Chamber Works by Frederick Block is now available [HERE].

Are you looking to promote an event? Have a news tip? Need to know the best events happening this weekend? Send us a note.

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.