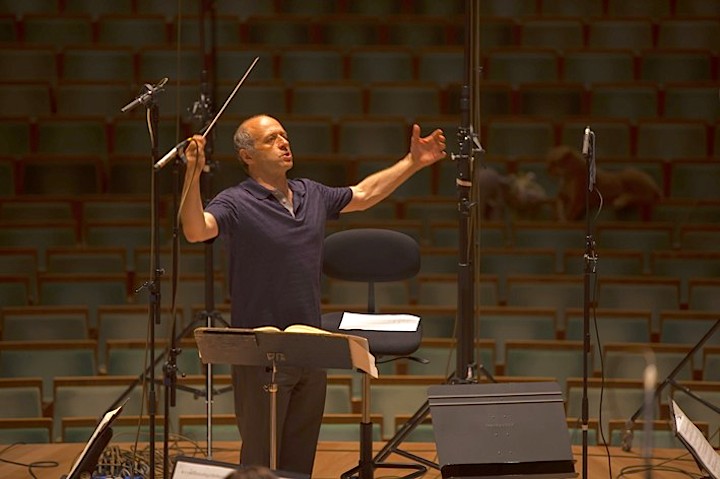

Hungarian conductor Ivan Fischer has been hacking an impressive pathway through the jungle of Gustav Mahler symphony recordings with his own impressively wrought interpretations. The most impressive yet is Symphony No. 5.

I often sit through Mahler symphonies wondering what the fuss is about with this composer, who pushed and pulled the envelope on what a symphony orchestra could and should express. The symphonies can sometimes sound like a mess of ideas and themes, tossed together like a salad with too many ingredients then dressed with too much vinegar.

Then great artsts like Ivan Fischer come along, bringing Mahler’s world into a shape and focus that feel absolutely right.

The most dramatic example of Fischer’s level-headed conception comes at the start of the second movement. In the score, Mahler tells his interpreters that the music needs to be played vehemently (“Mit grösster Vehemenz”).

Most conductors, rightly, take this as license to let ‘er rip, assaulting everyone in the concert hall with a barrage of noise.

Rather than noise, Fischer holds back, focusing instead on a laser-cut sharpness to the sound that gets to the point without actually pounding the listener’s head on an anvil.

Anyone can play loud, but giving the impression of loud without actually being so is the work of a magician.

There are many other treats in store here, too. The sugarplum dance of Fischer’s third-movement Scherzo and the pinpoint precision of the fugal passages in the fifth (final) movement are cause of ear-to-ear grins.

The remarkable four-movement Adagietto hangs suspended in time and space, a marvel of delicate artistry, yet it never loses momentum. That’s miraculous.

Among the many other things going on in Mahler’s life in 1901, when he began working on this piece, he was studying the counterpoint of J.S. Bach. Seen in the light of this obsession, the musical structures in Symphony No. 5 make perfect sense. Fischer does them full justice and, like the best Bach interpreters, remembers that the music must still sing and dance — and not just in the obvious places.

Who cannot love anything that in this tweeting, texting world forces us to voluntarily shut down for an hour and 15 minutes to contemplate an alternate universe of pure form.

You’ll find all the details on this album here.

John Terauds