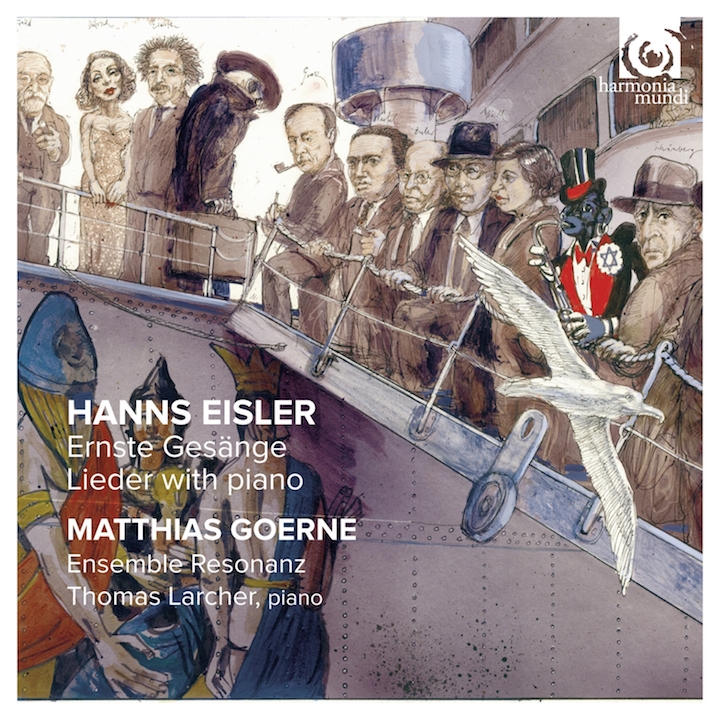

A compelling new album from Harmonia Mundi has baritone Matthias Goerne at the height of his powers making a strong case with pianist Thomas Larcherfor the music of 20th century composer Hanns Eisler.

Who?

It was only after appreciating the composer’s fine artsongs and marvelling at one of the best 12-tone piano sonatas I have ever heard (not faint praise, in case that’s what it reads like) that I wanted to know who this man was. Why was it that someone of such remarkable composerly craft could be so obscure only two generations after his death?

Well. It turns out that Eisler’s was the pen behind the national anthem of the German Democratic Republic — the one that wasn’t democratic; the one that built walls and fences and shot people who tried to climb them.

If we were looking for a poster boy for the vagaries of Fate, Eisler would be a prime candidate.

He was born in Leipzig in 1898, and went to school in Vienna. He was the right age to fight in the trenches of World War I on the losing side. He then returned to Vienna to study with Arnold Schoenberg.

Having hooked up with the It Composer of the day, Eisler dedicated his first piano sonata to Schoenberg. Built around a formal Classical style, it is a marvel of thematic development — in the required atonal idiom. With Larcher’s assured help in bringing it to life, this sonata is one of the rare examples of 12-tone music that has a connection to the viscera of humanity.

The piece was a success, and gave Eisler’s budding career a huge boost. He went off to Berlin, inspired by the Communist movement to write music celebrating the proletariat — and collaborating with Bertold Brecht.

Then came the Nazis. Eisler fled, eventually finding haven in Hollywood, where he seems to have done well. But then his name showed up at the top of the list of suspect leftie thinkers at the start of the Communist witch hunts in 1948. It didn’t take long for him to be deported, despite pleas from everyone who had worked with him.

He found refuge in East Germany after the Iron Curtain had been firmly drawn into place in the late 1940s. He continued to compose, but being on the wrong side of history ensured that he pretty much ceased to exist in western Europe and North America.

Goerne and Larcher have assembled a powerful sampler, an eloquent case that we should give Eisler another chance. (Goerne also recorded Eisler’s Hollywood Songbook a few years ago.) The first Piano Sonata is the only non-vocal work on the new album, which is devoted to artsong and cabaret pieces spanning Eisler’s career.

The opening seven-Lieder cycle, Ernste Gesänge, is his last major composition, from 1961. By this time, he had settled into a flexible tonality. The music is at once spare and lush — and at times heartbreakingly beautiful, especially the way the chamber orchestra Ensemble Resonanz plays it. There are clever little quotes from pre-World War II German music tossed in here and there, for anyone who wants to play a little game of trivial pursuit.

Because this is a selection of works from a composer whose style and subject matter evolved over time, most people will not identify with everything on this album. The compelling reason to get it anyway is the total commitment of all the interpreters to make this music sound as fine as it can possible get.

You’ll find precious little extra detail as well as some audio samples here.

There is an International Hans Eisler Society based in Berlin with a website that provides all sorts of extra information, including available scores and other recordings. There are also links to further reading, including a substantial number of books. You’ll find it here.

Here is Eric Schneider accompanying Goerne in “Die Heimat” from the Hollywood Songbook album:

Digging around YouTube, I found a recording of Ernste Gesänge, sung by lyric baritone Günther Leib and conducted by Günther Herbig, who would become music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra after he left East Germany in the mid-1980s:

John Terauds