I’m tone deaf. I can’t sing. It’s usually accompanied by a smile or laugh, but the message is both clear and absolute. And wrong.

Lorna MacDonald is Professor of Voice Studies and Vocal Pedagogy at the University of Toronto, and she puts it even more strongly. “That’s a blatant lie.”

Of all creative endeavours, singing is perhaps the most poorly understood. To the chagrin of vocal teachers everywhere, singing is the one pursuit where you will be told, you can’t sing, so don’t bother. Parents will readily pony up the resources for acting lessons, or soccer, but when it comes to the ability to sing, many people are still under the impression that it’s something magical – you either have it, or you don’t.

A study of undergrads at Queen’s University, found that about 17 percent reported themselves as being tone deaf. It’s such a common fallacy in our society that it has led to a world of singers — the small minority — and non-singers — the vast majority. But is that really based in reality? Science — and those vocal teachers — say no.

Sean Hutchins is the Director of Research at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music. His lab looks into how music affects the mind, and how the mind affects music, in essence. He calls singing a “structured coordination of vocal muscles” at its most basic level. “Just like any type of muscular activity, it’s amenable to practice. We know that practising motor control can help. You can certainly learn to be better.” As he points out, speaking is already a form of muscle control. So, why is it that our society has put singing into such a rarefied category?

“Part of the reason that there has been a source of anxiety over singing is inadequate music education.” He points out that in older generations, in particular, the sole emphasis was on performance. When school children who couldn’t naturally hit the right notes, rather than training them, they would simply be told to mouth the words, and not sing at all. “There’s no better way to make sure someone is bad at something than to tell them they can’t do it.” In contrast, at the Conservatory, they’ve studied children who begin singing lessons, and even a year of instruction produces definitive results.

Monica Whicher, a teacher at the Royal Conservatory’s Glenn Gould School, Lecturer: Voice Studies at the University of Toronto, and an active performer (soprano) grew up in a small town with a mother who was a vocal teacher. She saw the fallacy of tone deafness firsthand from an early age. “Singing is not this far off, unattainable thing. After one or two lessons, they changed their minds.”

She also quickly understood the need for adequate training. “People want to enjoy the way they sing,” she says. “The obvious benefit of instruction for non-professionals is better confidence.” Monica points out that singing instruction is a process, and that you can’t push for it all at once. “You have to get your ducks in a row, and understand what those ducks are.

Lorna MacDonald cites breath, posture, and vowels as the essential elements that are integral to vocal training for anyone. “It’s very much a physical process,” she explains. “Our larynx isn’t necessarily made to create those beautiful sounds, any more than our legs were designed to kick soccer balls.”

It’s about physical conditioning, in other words, and exploring the interior architecture of muscles and bodily forms that produce the sound to improve coordination. “We get to know our bodies well,” she says, “what we have control over, and what we don’t have control over. When you learn an instrument, you have to know how to put it together. In singing, we have an instrument we can only sense.”

The tongue can be trained to move more loosely, and the pharynx can be manipulated into various shapes. Singing is muscular, aerodynamic, in that it involves control of breathing, and also involves diction, the same process that is used for language. It’s also about artistry, drama, and emotion. Vocal instruction can involve a number of strategies. Some students need to know the precise physical details of how to create each sound, while others work better with imagery, and still others with verbal explanations.

It’s not just about working with the vocal processes, though. Singing ability is also dependent on getting adequate sleep and nutrition, and overall health. “You have to live your life as an artist,” MacDonald says. “We have to teach to the whole person.”

She suggests that thinking about what styles and genres you’d like to sing, and your ultimate goals as a singer are a good place to start. “It’s so important that it comes from a place of communication — not to be famous.”

But, what if you really are tone deaf?

In reality, people with congenital amusia, or the innate inability to hear pitch properly, form a very small percentage of the population. The study of amusia is still quite recent, but estimates put it at no more than 1.5 to 4 percent.

The Montreal Battery for the Evaluation of Amusia (AMUSIA) is a widely acknowledged protocol that is used to standardize and evaluate it. Professor Isabelle Peretz (Department of Psychology, Université de Montréal) is the Canada Research Chair in Neurocognition of Music and founder and Co-Director of the International Laboratory for Brain, Music and Sound Research (BRAMS), jointly affiliated with the Université de Montréal and McGill University, among many other accolades and positions. She and her lab are doing the pioneering work on musical ability that has led to the now widely used test.

The AMUSIA online screening test was first published in 2008, and is available for anyone who wants to take the screening here.

The research, while still ongoing, does seem to suggest that musical ability, and amusia, are congenital, at least to a degree. It seems to involve abnormal connections the right hemisphere of the brain, along with other specific areas. But, researchers have also posited that genes alone don’t provide the whole answer. There is some evidence that growing up in a musically rich environment can actually counteract an inherited propensity to amusia, and that the brain’s ability to process music does depend not only on that genetic hard wiring, but individual experience with, and exposure to, music as well.

In essence, amusia testing looks for evidence of faulty pitch perception. That’s the difference. Someone with clinical amusia actually can’t hear variations in pitch. There are also subcategories, such as receptive amusia — the inability to hear harmony — or musical alexia — the inability to process rhythm notation. If you can hear the notes, but just not reproduce them, that’s common garden variety bad singing, and the good news is, it can be improved with the right training.

“If I’m tone deaf, why do I love music so much?”

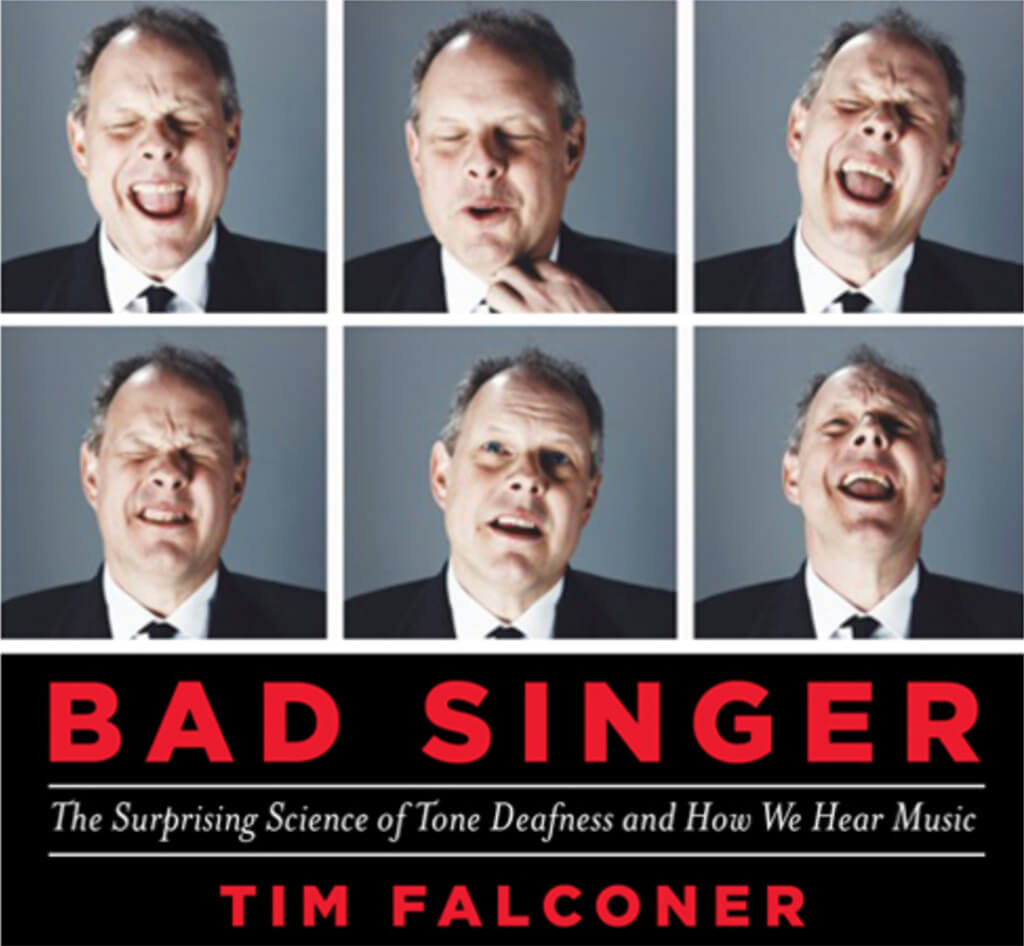

Toronto writer and professor Tim Falconer is a bona fide amusic, but that hasn’t stopped him from pursuing the art that he loves. He documented his adventures in music in his book Bad Singer: The Surprising Science of Tone Deafness and How We Hear Music (Anansi Press, May 14, 2016).

“I’ve always been a huge music fan, but I thought I was tone deaf,” he says. But, he was left with a question. “If I’m tone deaf, why do I love music so much?” Although he’d been encouraged by musical friends who insisted he only needed the right training, he went to Peretz’ lab in Montreal for testing. “You’re a classic amusic,” she told him.

His intrepid vocal coach, Micah Barnes, insisted that his singing could still be improved, “Never mind what the scientists say.”

Barnes and Falconer persevered. The results? In Tim’s talks about the book, he plays recordings of singing in the shower before and after training. “Everyone says I’ve improved — but I’m still terrible,” he laughs. Nonetheless, he’s performed at a private house concert, and no one booed him off the stage.

Some amusics can be trained to improve their singing ability, but it works differently. Tim describes it as, “I can tell when I’m off, it just feels off.” Training acts as an exercise in muscle memory.

In extreme cases, a little delusional thinking can help. Florence Foster Jenkins was a Manhattan heiress in the early 1920s to 1940s who dreamed of being an opera singer, and was somehow entirely convinced of her talent. There are a smattering of Youtube videos that attest to the fact that she was, let’s say, entirely lacking in training. Still, she went on to become a cult favourite of the NYC music scene, and even counted people like Cole Porter and Sir Thomas Beecham among her fans. Her wealth allowed her to rent Carnegie Hall for a night, and so she had her dream debut there at age 76.

It’s not that everyone will be headlining at The Four Seasons with the COC — or Carnegie Hall. But, a society of amateur singers will be that much more interested in the talents and performances of masters of the craft. There are signs that the idea of singing for everyone, at every level, is catching on, particularly in Canada. Toronto alone is home to several non-audition community choirs like Choir! Choir! Choir! In fact, a recent survey suggests that about 10 percent of Canadians participate in a choir or other singing group — more than play hockey.

“There’s this added benefit of finding communities of people who love it too,” adds Monica Whicher.

Sean Hutchins links the popularity of community choirs to things like chanting and singing at sports events. When we’re singing along with others, the anxiety tends to be eased. “If you put people in the right context, almost anyone can sing.” Putting people together seems to be the key. “It’s easier to sing along with other voices than with another instrument,” he notes. He also points out a phenomenon he calls “vocal generosity”. As listeners, we’re far more forgiving when a vocalist is off by a quarter note or so than, say, a violin that’s slightly out of tune.

So why sing, in the end? Professor MacDonald puts it best. “You contribute beauty to the world,” she says. “It’s never a stagnant instrument.”

[Corection, Oct 27, 2017. A previous version had misspelt Sean Hutchins’ name]

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and reviews before anyone else finds out? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter for all the latest.

- THE SCOOP | Not-For-Profit Euterpe: Music Is The Key Received Three-Year Grow Grant - April 24, 2024

- THE SCOOP | Flutist Arin Sarkissian & Percussionist Andrew Busch Make History With 2024 Michael Measures Prize Wins - April 24, 2024

- PREVIEW | The Works Of Barbara Strozzi & Maddalena Casulana Come Under The Spotlight In Apocryphonia’s Next Concert - April 23, 2024