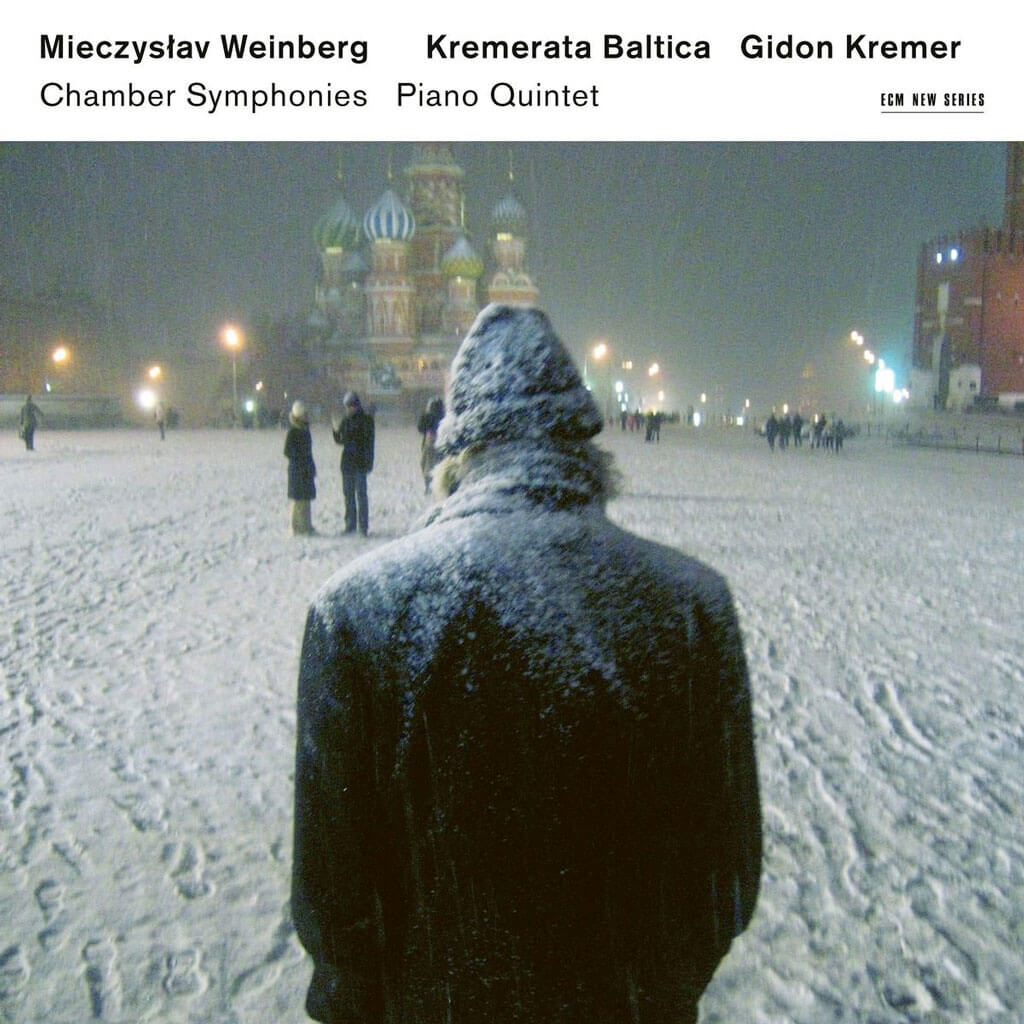

Mieczyslaw Weinberg: Chamber Symphonies (ECM)

★★★★ (out of five)

When I first started writing about Weinberg quarter of a century ago, there was no consistent western spelling of his surname (mostly printed Vainberg) and his first name was given as Moisei (pronounced Moshe), consistent with Soviet policy of identifying racial minorities. As for the music, it was unknown beyond the Soviet bloc, where it was more familiar to musicians in private performances than it was to public audiences. Today, thanks largely to proselytism by Gidon Kremer and his friends, Weinberg is no longer obscure but a musical giant, waiting to be discovered.

The musician closest to Shostakovich — each was first to see the other’s newest score — Weinberg fled Poland after the 1939 German invasion, was jailed in Stalin’s anti-Semitic purge and emerged as a vital creative force in his friend’s shadow. The early Weinberg works — his 1944 piano quintet and first string quartets — track whatever Shostakovich was doing at the time, a kind of rabbinic commentary with an individualist twist. Admirably prolific, he wrote more than 20 symphonies, 17 string quartets and several operas of which The Passenger has become, in the last decade, an international fixture.

The chamber symphonies came about in the late 1980s towards the end of his life when, fed up with writing unperformed symphonies, he revised three 1940s quartets for string orchestra and added an original fourth when he liked what he heard. The music clings to late Mahler — the third chamber symphony is almost an exegesis on Mahler’s Tenth — and the mood is morose. You can almost hear the Soviet Union disintegrating as backdrop. But there’s an appealing survivalism to Weinberg’s music, an intimation that if he could survive Hitler and Stalin no force in history would subdue him again.

Kremer plays a mesmerising lead violin in the second chamber symphony, where my ear caught hints of Britten’s Peter Grimes, and Mirga Grazynte-Tyla leads the fourth chamber symphony, which adds clarinet and triangle to the string ensemble. I was not convinced on first hearing by Kremer’s orchestration of the riveting 1944 piano quartet, but it’s growing on me, as it should on you. The music is indelible. Weinberg is now a must-know composer.

Mieczyslaw Weinberg: Chamber Symphonies (ECM) is available at iTunes and Amazon.com.

For more weekly reviews by Norman Lebrecht, click HERE.

#LUDWIGVAN

- LEBRECHT LISTENS | Two Releases Of Elgar Symphonies To Compare - April 19, 2024

- LEBRECHT LISTENS | Jordan Bak’s Cantabile For Viola Reveals The Neglected Instrument’s Beauty - April 12, 2024

- LEBRECHT LISTENS |David Robert Coleman & The Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra Reveal The Charms Of Walter Kaufmann - April 5, 2024