Part two in our series about hearing for music lovers, we look at the difference between hearing and listening.

It may seem self-evident that music lovers and music makers need good hearing to help enjoy the sounds that they love. But the ability to hear does not guarantee the ability to listen. Hearing is the ability to perceive sound by detecting vibrations in the air. Listening is the ability to pay attention to particular, specific sounds by discriminating between meaningful and desirable sonic input and extraneous noise.

Two books, both by Toronto authors, that brilliantly elucidate sound and listening are The Brain’s Way of Healing, by Norman Doidge, and When Listening Comes Alive by Paul Madaule. The first mentioned describes several innovative treatments that emerge from the brave new world of neuroplasticity. Doidge, who is a cross-appointed faculty member of the Music and Health Research Collaboratory at the University of Toronto, concludes his book with a chapter on how sound and music can be used to heal. Paul Madaule, whose life was transformed by the remediation of his listening problems, is profiled in that chapter. Madaule is also the Director of The Listening Centre in Toronto, where sound stimulation programs are used to help musicians improve their performance, as well as to relieve children and adults struggling with conditions that involve listening deficits, including learning disabilities, autism, attention disorders, and other maladies.

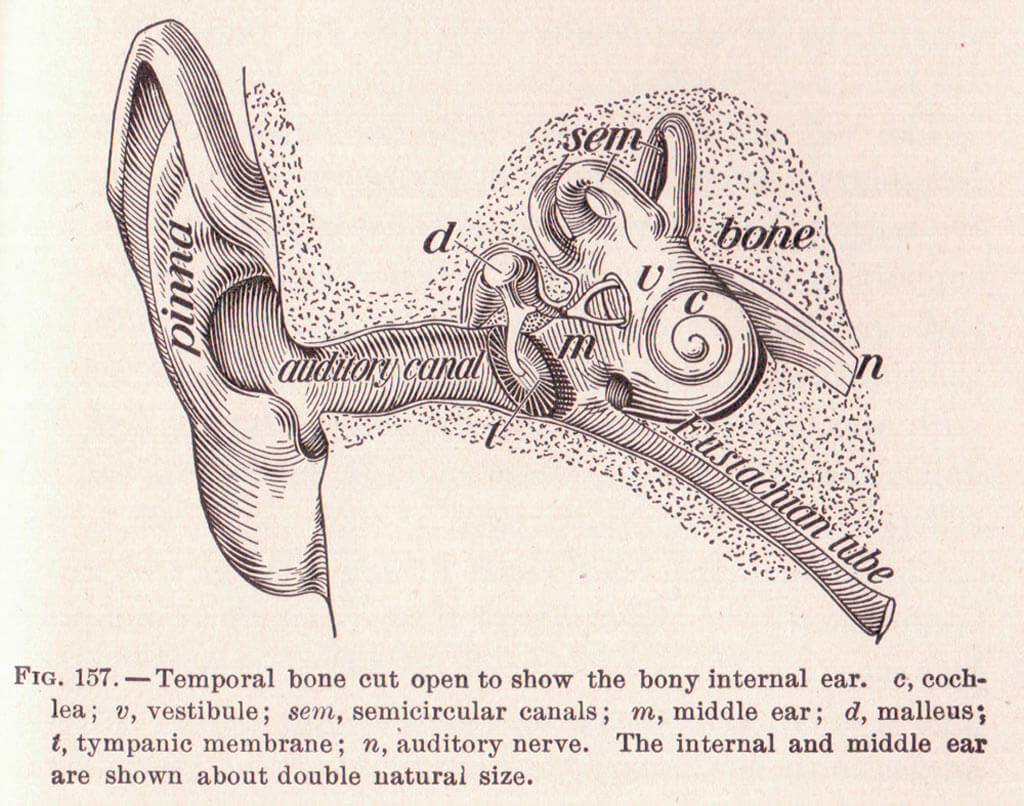

These two books made me aware that those protuberances on the sides of my head do much more than provide tissue from which to dangle earrings. To mention only three: Ears are impressively hard-working organs, containing one muscle that is a constant state of tension, the stirrup muscle which protects us from external and internal noise from our own bodies; ears, through the vestibular system, help us resist gravity, and facilitate posture, balance, gait and coordination; and ears mature much earlier than our other organs, fully functioning in utero by four months, giving us five months of private listening to our mother’s voice and bodily processes.

But functional ears don’t guarantee effective listening any more than eyes guarantee accurate sight or hands guarantee dexterity. When listening is dysfunctional, however, it often goes undetected because the process takes place internally and doesn’t show. Instead, the compromised listener is characterised as inattentive, lazy, unresponsive, emotionally flat, rude, unmotivated and worse. We are drastically unaware of the impact our ears have on our character.

The highly original, innovative and somewhat controversial French otolaryngologist, Alfred Tomatis, (1920-2001) was the first to realise that we hear with both ears, but we listen most effectively from our right ear. Individuals, who listen from their left ear, or with both right and left, cannot use sonic data as rapidly or effectively as others. Tomatis developed a program to stimulate the ears with sound frequencies that bolster right ear dominance.

The son of an opera singer and musical himself, many of his early discoveries were a result of treating singers whose vocal problems were not due to larynx deterioration as they thought, but because the range of sound frequencies they could hear had diminished. Recognising that these performers could not reproduce a sound that they could no longer hear, Tomatis created specialised earphones and a program of sound stimulation plus vocal exercises that optimise the range of frequency that can be perceived.

The core of the program is listening to Mozart violin compositions, with the lower frequencies filtered out, to enhance the perception of the higher frequencies, followed by filtered Gregorian chants, which are very rich in high frequencies. These soundtracks have an eerie, distant quality as if broadcast from a radio station on Mars, but they are not unpleasant. The music gives the ear muscles a vigorous workout, so it’s common doze off while listening. (This may be the one form of exercise you can do while taking a nap!!) A series of ear-voice exercises are added into the listening process, starting with bone-conduction humming exercises that entail reproducing tones heard through earphones. It takes intense concentration; erect posture, controlled breathing, careful shaping and placing of the mouth and tongue, and attention to fine details to generate the desired state of vibration and resonance. Like many interventions that draw on neuroplasticity, it requires paying close attention and results in incremental progress. When I tried the exercises, sitting on a height-adjusted stool in front of a chart of vowel sounds, a mirror, and a microphone, I felt like Eliza Doolittle being put through her paces by Henry Higgins. With persistence, however, I will be able to enjoy the feeling of resonance and vibration that makes chanting both relaxing and energising.

It is generally accepted that hearing loss is an inevitable part of ageing. It’s also known that hearing loss is occurring earlier in life than it once did. While buying hearing-aid stock seems like a sound investment, I have to wonder whether strengthening our listening ability might be a preferable intervention in many cases. One general rule of neuroplasticity is “use it or lose it” and we tend to lose skills that we think are dormant but functional unless we make a demand on them. We may think we are listening, but if we aren’t challenging our listening ability, it could be silently declining.

It’s worth being aware that directing conscious effort at listening can bolster it. Beyond that, improving listening enhances every other activity where sound and attention to it is critical: learning, public speaking, conversing, obtaining and imparting information and most of all, being receptive to the words and other sounds of communication, including cries of need of our families, friends and community. Social engagement, which is considered essential to delay dementia, depends on our ability to listen to each other. It’s time to put listening fitness on the agenda.

For Hearing For Music Lovers (Part One), see here.

#LUDWIGVAN

Want more updates on Toronto-centric classical music news and review before anyone else finds out? Get our exclusive newsletter here and follow us on Facebook for all the latest.