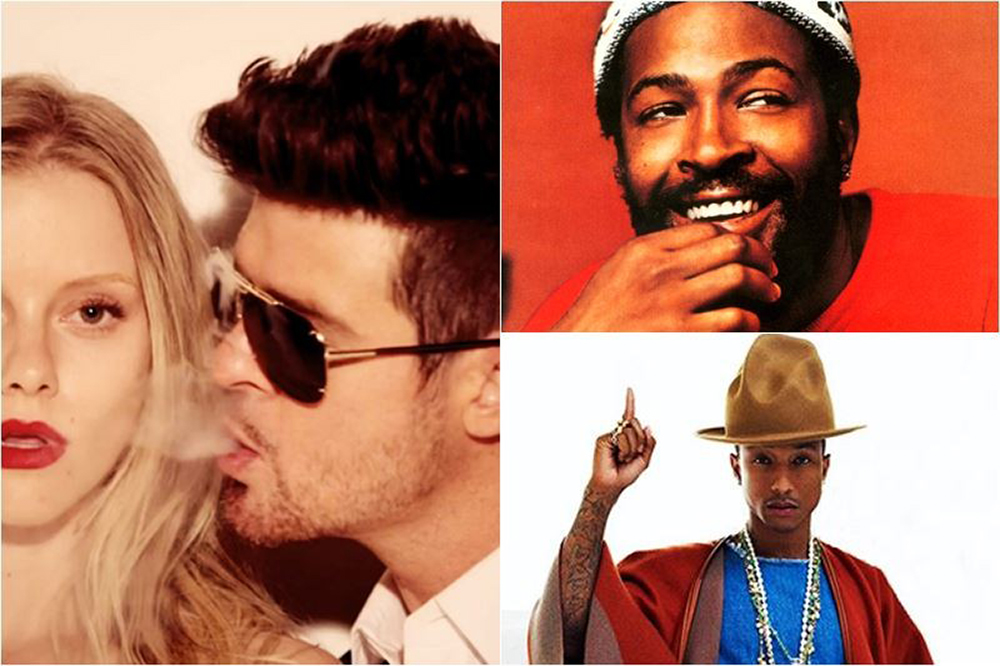

The verdict is in. Marvin Gaye owns a certain “style” of music. And now thanks to legal precedent, in the US anyway, if you re-create it like Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams did, you could end up owing a mountain of money to the Gaye estate – in this case $7.4 million.

For those who need to get up to speed, you can hear the side-by-side comparison of Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams’ Blurred Lines, and Marvin Gaye’s Got to Give it Up in the video below:

That this case even made it to court was surprising to many people; this case has been called everything from “pretty unusual” to “baffling” to “dangerous.” Although the backing tracks for the tunes sound very similar, the general way a backing track sounds has never been grounds for copyright infringement in the US. Successful copyright disputes have always hinged upon at least one identical element shared between two songs or recordings, whether it be a melody, a set of lyrics, or the unauthorized use of an audio sample. The melodies, lyrics and instrumental performances in Blurred Lines are not identical to any element in Got To Give It Up, nor was any audio from Gaye’s recording sampled for Blurred Lines (it would not have mattered, anyway, since Gaye’s family only owns the song, not the recording.)

So what was the evidence against Blurred Lines? According to Kate Conger at Ratter, the musicologist hired by the Gaye family presented the following slide in court in an attempt to prove more than a passing similarity between the two songs:

With this slide the musicologist puts both melodies in the same context and proves that they share the following elements:

- a: a melodic fragment of three repeated notes (but not on the same scale degree)

- b: a melodic fragment consisting of the 5th, 6th, and 1st scale degree in upwards motion in eighth notes

- c: a rhythm of six repeated eighth notes preceded by a rest

- d: a melisma (a phrase where one vowel sound is continued over more than one note) that contains a descending fourth (the second b)

Although this is compelling at first glance, these elements are far from novel, and Pharell and Marvin Gaye are hardly the only songwriters to use this material. Take those a and b melody fragments of Got To Get It Up, for example, notated here as “5-5-5″ and “5-6-1.” Together they are also the melody of the opening phrase of the chorus to Janet Jackson’s song Runaway:

They’re also basically the opening piano melody to Smokey Robinson’s You Really Got a Hold On Me:

(*In this case phrase a is reduced to one note on the 5th scale degree, however phrase b continues onto the 2nd and then 1st scale degree, as is the case of Got To Give It Up.)

That eighth note rhythm indicated as c is also extremely common,which makes me wonder why it’s even being considered as part of the lawsuit. Here it is in Beauty and The Beast:

Here it is in Old Time Rock and Roll:

And in the opening phrase of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 21 (Waldstein):

These are common melodic and rhythmic ideas. I have only been working at this for about an hour and have already came up with one example that is an exact match for the Gaye a, b and c; one match for b and c that contains a significant fragment of a, and three rhythmic matches for c. This can be contrasted with the Sam Smith / Tom Petty plagiarism case, where my $180 prize for a third exact match that predates those songs has yet to be claimed despite a response from my friends that would lead me to estimate at least 15 man-hours have been spent looking for one.

As for the material labeled d and the second b, these fragments should be considered irrelevant; melismas like this are frequently improvised, and these are two different melismas despite the fact that they share a common interval. You can’t copyright the broad idea of including a melisma that contains a descending fourth.

The songwriting copyright case that set the modern precedent in the United States was Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs, in which George Harrison was successfully sued over the similarities between My Sweet Lord and He’s So Fine, a hit song from 1962. Both of these songs have similar three- and five-note melodic fragments as well as the same chord progression. In his ruling, the judge decided that using the same three- and five-note fragments on their own would not have been novel enough to be copyright infringement, but that the “four repetitions of A, followed by four repetitions of B” shared by each melody “create a highly unique pattern.” (It’s actually four and three; his description in the ruling is incorrect.)

So the copyright was violated in the Harrison case not because a few notes were the same, or because the tracks sort of sound the same, but because specific melodic fragments were repeated the same way in each song for a total of twenty-seven shared notes in a row between the two songs. This is clearly not happening with Blurred Lines; there are only three (arguably five) notes that match each other exactly, and they are neither novel nor repeated throughout the tune.

With the verdict going in favour of the Gaye family, things are about to get very interesting. The Gayes’ musicologist has chopped the music up into pieces that are so small that it will likely have a chilling effect on songwriting in the United States. If three common notes and a similar-sounding backing track is all that is needed to successfully sue someone, then the floodgates of litigation are about to swing wide open.

- FEATURE | An Analysis of the Evidence Against “Blurred Lines” - March 12, 2015